Study: Significant Differences in Juul’s Chemical Make-up (and Health Risks) in U.S. and Europe

The chemical make-up and nicotine levels of the e-liquids used in Juul vaping products differ greatly for consumers in Europe and those in the U.S. and Canada, and a new study shows that each version brings a separate set of potential health risks.

The results of the study - a collaboration between researchers from Yale and Duke University - are published June 27 in the journal Tobacco Control.

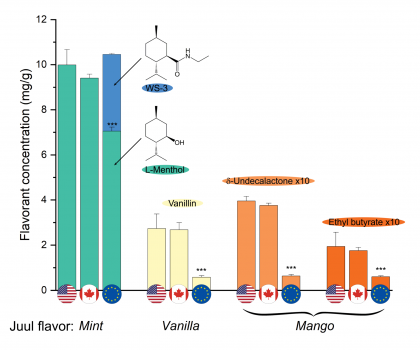

In Europe, Juul e-liquids have a lower level of both nicotine and flavor chemicals than what’s found in Juul’s products sold in the U.S. However, certain flavors of the European e-liquids contain WS-3, a synthetic coolant with the chemical name n-ethyl-p-menthane-3-carboxamide. Although WS-3 has been approved for use in foods and is mostly used in chewing gum, very little is known about the health impacts of WS-3 when inhaled.

In Europe, Juul e-liquids have a lower level of both nicotine and flavor chemicals than what’s found in Juul’s products sold in the U.S. However, certain flavors of the European e-liquids contain WS-3, a synthetic coolant with the chemical name n-ethyl-p-menthane-3-carboxamide. Although WS-3 has been approved for use in foods and is mostly used in chewing gum, very little is known about the health impacts of WS-3 when inhaled.

On the other hand, because U.S. e-liquids contain more flavorants overall, more chemicals such as emulsifiers seem to be required to keep the liquids stable. Similar to WS-3, there has been little research about their health effects when inhaled.

“While the U.S. and Canadian Juul e-liquids contained an emulsifier, the European ones did not,” said Hanno Erythropel, the study’s lead author and an associate research scientist in the lab of Julie Zimmerman, professor of chemical & environmental engineering. “Emulsifiers ensure that mixtures don’t separate into their individual components as oil and water would. Because the higher flavorant concentration leads to more intense flavors in the U.S. and Canadian products, the use of the emulsifier is likely required to create a stable product. While approved for use in food, it is unclear whether the emulsifier is safe to inhale.”

The differences are due partly to regulations: European Union regulations cap e-liquid nicotine concentrations at 1.7% or 20mg/mL, while U.S./Canadian products are sold with nicotine contents of 5%, 3%, and 1.5% (Canada only). With lower levels of nicotine, the products may require lower levels of flavor chemicals to mask nicotine’s bitterness. Cultural preferences, though, may also play a role.

“Menthol cigarettes aren’t as popular in Europe,” said co-author Sven-Eric Jordt, associate professor in anesthesiology at Duke University. “Mint in general is not very popular in tobacco products in Europe, so Juul partially replaced the menthol with WS-3, which has a cooling effect, but doesn't smell like menthol.”

Research suggests that menthol facilitates the inhalation of nicotine by masking its unpleasant taste. Previous studies have shown that mice exposed to mentholated smoke have higher nicotine levels in their blood, likely because they can consume more of it without an aversive response. WS-3 likely has the same effect.

“It is unclear whether inhaling WS-3 is safe,” Jordt said. “There's safety data on it for food, including limits on how much can be added to food. Research suggests that too much of it can lead to kidney and liver damage. The lung is generally more sensitive than the stomach and digestive tract, so the fact that this is added without any knowledge of respiratory safety is a big concern we have.”

Erythropel noted that there’s no reason to believe that there’s any immediate danger in using products with these chemicals, but consumers should be aware of the unknown factors.

“The question is what happens over the long-term,” he said. “What are the effects of repeated daily inhalation over the course of months or years? It’s likely a question of chronic effects, rather than acute effects.”

In addition to Erythropel, Jordt, and Zimmerman, the study’s co-authors are Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin and Stephanie S. O’Malley in the Yale tobacco center of regulatory science (TCORS) housed in the department of psychiatry, and Paul Anastas in the school of public health at Yale.

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant numbers P50DA036151 and U54DA036151 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP), and grant R01ES029435 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Go here to see the full study.