Students Work With State on Making Trains Safer During COVID-19

Reducing the spread of coronavirus on railcars is a complicated matter, but with the work of two students, transportation officials are a few steps closer to safer travel.

Marley Macarewich ‘22 and Nathan Pharr ‘22 both had summer plans that fell through, due to COVID-19 - she sought out internships in patent law, and he was going to do some architecture-related work. They both turned to the SEAS 2020 Summer Design/Research Scholars, a program designed specifically around the unique circumstances that students are facing this year. SEAS Deputy Dean Vincent Wilczynski, who organized the internship program, said the idea for it came about as a way to mitigate the loss of internship, research, and academic opportunities that many students are experiencing this summer.

Of the various projects offered, Macarewich, a chemical engineering student, and Pharr, who majors in environmental engineering, decided to tackle the timely problem of mitigating the spread of COVID-19 on train cars, a project that they worked on with the Connecticut Department of Transportation (DOT). Soon after signing up for the project, they met with top DOT officials, and then took a deep dive into the subject.

Of the various projects offered, Macarewich, a chemical engineering student, and Pharr, who majors in environmental engineering, decided to tackle the timely problem of mitigating the spread of COVID-19 on train cars, a project that they worked on with the Connecticut Department of Transportation (DOT). Soon after signing up for the project, they met with top DOT officials, and then took a deep dive into the subject.

“We came in not knowing anything about this, really, so there was a lot of background reading, reaching out to professors and experts in the field regarding aerosols and infectious diseases, and then seeing how all this could be applied to the railcar itself,” Pharr said.

Assistant Dean for Science & Engineering Sarah Miller was the students’ mentor for the project. She said their work “represents the best of Yale Engineers.”

“They approached this critically important project with optimism, determination, and an inspiring spirit of collaboration,” she said. “Their hard work and fortitude resulted in extremely helpful guidance that will keep Connecticut and all its rail riders safer.”

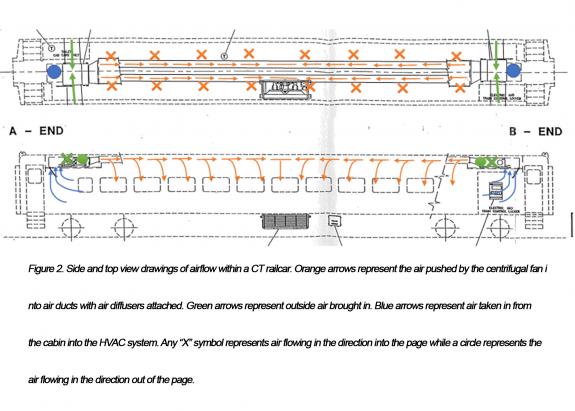

The DOT provided the students with background information on the railcar layouts, the HVAC system, and the electrical wiring that goes throughout the layout of the car itself. One of the first things they learned was that the issue is a lot more complicated than it initially appeared.

“There were things that I thought, ‘Oh, this will be easy - slap on a HEPA [high-efficiency particulate air] filter and call it a day!’” Macarewich said. “Then, after looking at all the diagrams and talking with experts around the world, we realized it’s not as simple as that.”

One complication is that the particular trains aren’t designed for the filters they had in mind. “We really had to question how we thought about air flow,” she said.

The amount of air changes on a railcar is much greater that what is seen in a typical room, such as an office. What that means in regard to infection risk, though, depends a lot on the occupancy levels on a railcar. Ridership has been low in recent months, so the infection risks have been relatively low, assuming all on board are following safety protocols. The work they’re doing is looking at the quality of ventilation when occupancy levels are back to normal, or higher.

After eight weeks, Pharr and Macarewich wrote a highly detailed 40-page report that they submitted to the DOT. Richard Andreski, the DOT’s bureau chief for public transportation, said the work “provided invaluable research on ways to reduce the potential transmission of COVID-19 on passenger trains.”

“Connecticut DOT is grateful for its partnership with Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science,” he said. “They dove into the problem as a true partner, listening to their client and taking the time to understand our operational challenges. Their efforts yielded practical, straightforward solutions to improve public safety that will be implemented across the state’s passenger rail system.”

Some of the best ways to mitigate the spread on the DOT’s trains, the students wrote in the report, is through many of the measures recommended for public life in general: everyone wears a mask on the train (face shields can be used as a supplement to, but not a replacement for, face masks); use seating charts and directional walkways to maintain social distancing; and help keep the public informed about the virus, its symptoms and how it spreads.

More specific to rail travel, they also suggest:

- Potentially creating a separate car for high-risk individuals

- Allow for extra ventilation time and maintain negative pressure in bathrooms, and properly clean and disinfect them. Also, maintain the positive pressure of the main cabin of the railcar

- Increase the outdoor air flow throughout the railcar to dilute harmful aerosols within the cabin

- Consider shields made of plexiglass or other materials for the backs of seats, while avoiding any significant interference with room ventilation

- Install portable air cleaners equipped with high-efficiency filters in railcars to reduce the spread of harmful aerosols

- Frequent use of approved disinfectants for frequently touched surfaces

- Increase the run time of the HVAC system or allow more time for particles to settle at the end of operation before cleaning and disinfection measures are carried out.

Longer-term solutions include designing a system that supports personal ventilation; installing new HVAC systems with high-efficiency filters; and choosing hard, nonporous, smooth materials for the surfaces in the railcar for ease of cleaning.

They recommend against using seat covers, as proper clearing would make them unnecessary, and against using UV technology to disinfect the cars due to the amount of time required, and the potential health effects.

Although the summer internship ended, their work on railcars continues. Prof. Krystal Pollitt, assistant professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health, was one of the scientists that Pharr and Macarewich reached out to in their research. When the three found that they were working on similar projects, they began collaborating outside the summer internship program. Now the two students are working with members of Pollitt’s lab and preparing a manuscript that will be submitted to a peer review journal.

In working with the DOT officials, Pollitt said their concern has less to do with redesigning existing railcars and more about how the next generation of railcars should be designed and built, not just with COVID-19 in mind, but better ventilation in general.

“One of the things we’re looking at is how we can get as much outdoor air as possible on these cars, and how can we increase the total amount of ventilation,” said Pollitt, who is also an assistant professor in chemical and environmental engineering. To that end, the students have developed strategies and graphs showing how air can be introduced at different points of the railcars to better distribute fresh air.