Students and Smithsonian Work Together to Increase Access

Thanks to the work of a team of undergraduate students over the summer, officials at the Smithsonian Institution have a number of new ideas for making sure that everyone can feel the full power of their exhibits.

“Think about a Civil Rights movement exhibit with music; then think of it without,” said Katherine Schilling, research scientist in Chemical and Environmental Engineering. “That powerful emotion is what the students wanted to make available to every visitor.”

The team of Alice Huang ’22, Josh Vogel ’22, Michelle Tong ’21, Melanie King ’23, Sebastian Bruno ’22, and Veronica Chen ’22 were part of the SEAS 2020 Summer Design/Research Scholars, a program designed to mitigate the loss of internship, research, and academic opportunities that many students experienced over the summer. The team was led by Schilling, who is also an associate conservation research scientist at the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH) at Yale’s West Campus.

The team of Alice Huang ’22, Josh Vogel ’22, Michelle Tong ’21, Melanie King ’23, Sebastian Bruno ’22, and Veronica Chen ’22 were part of the SEAS 2020 Summer Design/Research Scholars, a program designed to mitigate the loss of internship, research, and academic opportunities that many students experienced over the summer. The team was led by Schilling, who is also an associate conservation research scientist at the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH) at Yale’s West Campus.

Roger Brissenden, Smithsonian’s undersecretary for science, noted that the institution is just beginning to reopen a number of its museum and exhibition spaces - a process that allows the opportunity to rethink accessibility to engage as broad a range of visitors as possible.

“What’s exciting to me about this project is that it's about six incredibly talented undergraduates who marshalled their design and engineering talents to tackle some of the trickiest challenges facing museums today,” said Brissenden, who oversees the science museums and science research centers as well as the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. “Accessibility is an incredibly important priority for the Smithsonian right now, especially as we move into a post-COVID, new normal time.”

One of the student teams worked on the exhibit “World on the Move: 250,000 Years of Human Migration,” which features an interactive token-based system of representing global human migration and its motives. In its current form, the exhibit is mainly visual, so the team created a way to help blind and low-vision patrons take part.

As part of the exhibit, visitors indicate where their families originated from, and why they moved to where they are now. The visitors insert a chip of a particular color (there are seven colors altogether, each corresponding to one of seven regions of the world) into one of seven transparent tubes. As the chips accumulate in the tubes, the visual effect is similar to a bar graph, giving an overall picture of visitors' family migrations.

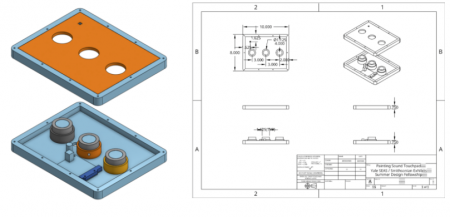

The students designed the chips with different textures and installed sensors to sort the chips by color. They also added a raised ridge to system components, such as its audio buttons, to help users navigate the system. Because everyone was working remotely, Veronica Chen and Sebastian Bruno each created a prototype from their homes out of cardboard and other materials available to them.

A second team of students worked on ways for patrons who are deaf or have hearing loss to experience the emotion of music and sound that are often critical to museum exhibits. For this, they drew inspiration from the work of filmmaker Oskar Fischinger, known for his abstract musical animations. In the students’ plan, users would stand in front of a Kinect, a motion sensor, to create musical and visual pieces. Visitors would also hold a touchpad that simulates heartbeats of various tempos, each one corresponding to a different emotion.

Both projects received praise from the Smithsonian officials.

Both projects received praise from the Smithsonian officials.

“The energy and the creativity, problem solving, the smarts and just the passion that you brought to these two challenges that we set you up with were really inspiring, and it gave us an extra boost as well during this time that is challenging for everybody,” said Susan Ades, director of Smithsonian exhibits. “Our team, working on ‘World on the Move’ and other sound-based experiences, will be very happy to take some of your ideas and run with them.”

Jeffrey Brock, dean of the School of Engineering & Applied Science, noted that the project was an example of people in SEAS making the most of a difficult time.

“You are all such a tribute to SEAS and this program is such an excellent opportunity,” he said. “I'm so glad we were able to turn a ‘forgotten summer’ perhaps into something that was really productive for everybody.”

Ivan Selin ’56, who was founding board chairman for the Smithsonian, as well as being a strong supporter of Yale endeavors, praised the students’ presentations. Even more impressive than the solutions, he said, was the students’ ability to confidently explain their work to a wide audience – including non-engineers – even as they spoke remotely on Zoom.

“This is why the CEID was set up 10 years ago - to bring engineers and non-engineers together and to get them talking and understanding each other,” he said. “That’s a big part of the Yale experience, and you’ve gone further than ever before in bringing together this integration of engineering, of design, and technology. Years from now, you’ll forget the technical details, but still remember the experience of engaging a general audience.”

One of the students involved, Alice Huang, said she originally planned to spend her summer in an internship related to her major of biomedical engineering until the pandemic shut down most of the programs she applied to. She then turned to the Summer Design/Research Scholars.

“Building our prototypes from the ground up allowed us the opportunity to immerse ourselves in the problem space and bring to life our vision of a potential solution for increasing accessibility in museums,” she said. “I also thoroughly enjoyed meeting and collaborating with the amazing professionals who made our project possible. I'm thankful we had the opportunity to get to know them, and exchange our (crazy?) ideas with them, and learn a lot from them in the process of creating our final products.

Josh Vogel said the program was “everything I wanted right when I needed it most” after his original summer plans were cancelled.

“I think the most rewarding part of the entire fellowship was actually getting to work on a project every day,” he said. “This was my first work experience in engineering and it was intensely validating to see how much I enjoy working in this field. It’s also inspired me to keep pushing through school because I know how much I’ll love what’s waiting on the other side.”

The collaboration is one example of a larger partnership between Yale and Smithsonian that was initiated in 2016 as a way to draw upon the institutions’ complementary strengths and to incubate innovative research and collaboration between the institutions. The Smithsonian has also worked with SEAS on previous projects. In 2017, the course Making Spaces had students working with Smithsonian officials on ways to incorporate technology into the renovation of Smithsonian’s Arts & Industries Building.