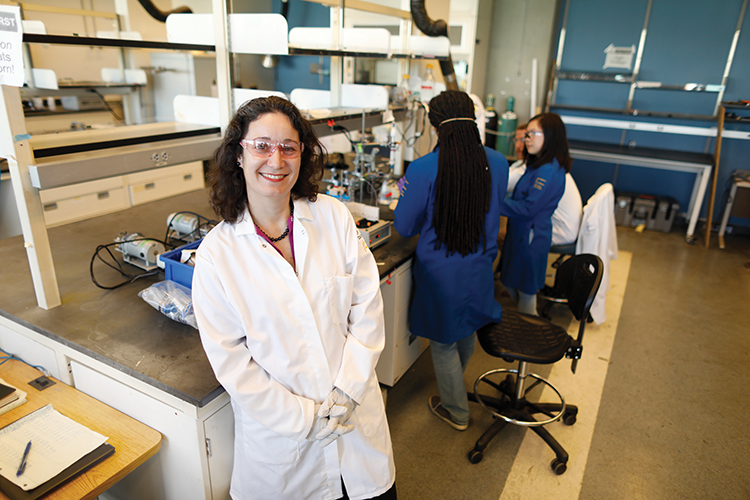

From a pioneer of Yale’s environmental engineering program to Drexel’s new dean

Earlier this year, Sharon L. Walker, Ph.D. was named Drexel University’s new dean of the College of Engineering. In 1999, she was one of five students to join Yale’s then-brand-new environmental engineering program, and she received her Ph.D. in 2004. She has since spent much of her career at the University of California, Riverside (UC Riverside), first as an environmental engineering professor, and then as interim dean of UC Riverside’s Bourns College of Engineering. She began as dean at Drexel Sept. 1.

We spoke with Dean Walker about what it was like being part of the first wave of a pioneering program, working with its founder Menachem Elimelech, becoming Drexel’s first female dean of engineering, and why students can’t be treated simply as “technical sponges.”

You were among the first recruited for Yale’s Environmental Engineering Program, which was part of the Chemical Engineering Department (since renamed Chemical & Environmental Engineering). What was that like?

I loved it so much — it was one of the happiest times of my life. I think most of us have some stage in life that you can pinpoint as your coming-of-age period, and I think my time at Yale was that.

There were three of us in the first class, plus two who had come the year before with Meny [Elimelech]. It was a very exciting time, although we had to prove ourselves because I think the chemical engineers hadn’t quite got their heads around the fact that these environmental engineers were going to be joining them, and what that meant in intellectually and scholarly ways.

How was it working with Menachem Elimelech, the Roberto C. Goizueta Professor of Chemical & Environmental Engineering?

Meny would put the pressure on — he wanted us to prove that the environmental engineers were just as good and rigorous students. He’s an amazing mentor — he expects an enormous amount of focus and hard work. You have to be a self-starter and motivated, but I always felt he was right there with me. He was devoted to his students and his lab — he would put in the hours with us. He was so quick to give feedback, you never got a break! You would send him a draft of the paper you had been working and laboring over for days and days, and hope you’d have a day to recover and breathe. He was such an early riser that the next day he would already have a draft, all marked up, and it would be sitting there on your desk waiting for you.

Do you still maintain a relationship with Yale?

One of the things that I have had such great pride in is not just being a graduate of the Yale program, but that I’ve continued to try to be an entry port and a recruiter for it. Over the years, I have sent four Ph.D. students to Yale, where a couple have recently finished, who have come out of my program at UC Riverside. I sent one Ph.D. student of mine to postdoc in the department at Yale, and there are currently two Ph.D. students at Yale in the environmental engineering program that were my undergraduates. I’ve actively mentored Yale students when they’ve reached out to me, both while they’re students and while they’ve started their academic careers afterward. A rich, wonderful community of students have come through that program, and I love to be engaged with it. And I’m looking forward to building a pipeline, not just from UC Riverside, but back and forth from Drexel.

At Yale, your research focused on water quality. It has since shifted toward the use of nanoparticles for food safety. How did that happen?

I’ve been working in that area for at least six years, so I’ve been ahead of when it was in vogue. Meny taught us that you take your fundamental tools, your fundamental knowledge and apply it to the emerging problems, so I’ve been able to be nimble and adjust what I do. In some ways, one could say I’ve been able to reinvent myself a few times because of that. The reality is that it’s all grounded in the fundamental tools that he taught us.

How has the transition been from teaching and research to administration?

One of the things I liked about teaching was working with the students and the transformation you see as they discover themselves intellectually. I think when you’re a dean, it has that same sort of effect, but on a bigger scale and bigger impact. All of those things that I loved impacting as a faculty member, I could do on a scale that was unimaginable — everything from infrastructure to policy to curriculum.

There’s always politics, but I enjoy people and I enjoy the fact that as dean that I can be an advocate for people and engage with people as a major part of my day. That’s just fun — I love working with people.

You are the first female engineering dean at Drexel. How has the field changed for women and underrepresented minorities?

When I was hired, I was one of four or five women on the faculty, and by the time I left UC Riverside 14 years later, there will be 19 women. One can argue that’s still low, but that’s really a transformation. Women have gone from being 5 percent of faculty to now about 14 percent of the faculty. I think that’s a very exciting trend, but there’s a long way to go. While I was interim dean, I hired almost 40 percent women in the last two hiring cycles. I’ve also doubled the number of minorities on the faculty. This is what I was saying — the platform of being a dean can change people’s lives. You can set a priority and steward these things. I’m not mandating certain opinions on the faculty, but there are ways that people in positions of leadership can set fundamental priorities and visions.

You’ve focused on helping students develop practical skills beyond academics. Why is that a priority?

One of the things I did at UC Riverside was teach a class called Professional Development for Chemical and Environmental Engineers. I loved teaching the class because it allowed me to work with students on their soft skills. At UC Riverside, there is a group of first-generation students, often from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. If no one in their family has ever had a white-collar job before, you can’t necessarily take it for granted that they know what to wear for an interview or how to tie a tie and other important skills, so there are a lot of students who needed a little extra coaching.

Teaching that class for a number of years allowed me to see how transformational the experience can be if we take the time to work with the students, not just as technical sponges, but to work on the whole person — a more holistic approach. Moving forward, I think that’s how we as educators need to be. We need to make sure that the students have the technical competency, but they must also have these soft skills to be capable of transforming themselves as the world changes — and it’s changing so fast.