Mehraveh Salehi Wins first inter-ivy 3-Minute Thesis Competition

Mehraveh Salehi has spent the last few years working on a thesis that combines neuroscience, statistics, and data science and challenges conventions in each of those fields. It also sheds light on longstanding mysteries of the human brain. Summarizing this work and its significance might seem a bit tricky. But allowed only three minutes and one image to do so, Salehi succinctly explained her work to a general audience at the first Ivy Three-Minute Thesis (3MT) last week, taking first prize.

Ph.D. students from Yale, Brown University, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Princeton University, and University of Pennsylvania (each won a smaller 3MT competition at their own university) competed at the April 25 event hosted by Columbia University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the United Nations.Yale’s participation in the event—the first time all the Ivy League schools have met up for the competition—was coordinated by several McDougal Offices, especially the Office of Career Strategy and the Graduate Writing Lab at the Poorvu Center.

Ph.D. students from Yale, Brown University, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Princeton University, and University of Pennsylvania (each won a smaller 3MT competition at their own university) competed at the April 25 event hosted by Columbia University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the United Nations.Yale’s participation in the event—the first time all the Ivy League schools have met up for the competition—was coordinated by several McDougal Offices, especially the Office of Career Strategy and the Graduate Writing Lab at the Poorvu Center.

The rules of the competition are pretty strict. No props are allowed (although a laser pointer is provided if needed), and timing is important - taking more than three minutes earns an immediate disqualification. The judges included representatives from the United Nations, the Lincoln Center, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and McKinsey & Company. The event was the idea of Hyun Ja Shin, director of graduate and postdoctoral career services at Yale’s Office of Career Strategy, and Kelly Ahn, the associate dean of graduate student career development at Columbia.

“We thought it would be a terrific way to showcase the fact that our Ph.D. students are not only excellent researchers but also skilled communicators, and are equipped for professional success in the workplace whether in academia or beyond,” Shin said.

They pitched the idea to the other Ivy Schools, many of which already had their own 3-Minute Thesis events, and everyone agreed that some friendly inter-Ivy competition was a great idea.

Salehi has been working for about five years on this research and had about six weeks to present it within the strict format. That meant spending a lot of time looking at her work from a broader perspective.

“I ran it past friends working on other topics and asked them for feedback,” she said. “I wanted to be sure that I was as clear as I could be about what I’m doing. I finally wrote down the whole script, and there was a lot of timing myself and going through it again and again and again.”

She also received help from the Office of Career Strategy and the Graduate Writing Lab at the Poorvu Center. There, she worked with Shin and Elena Kallestinova, assistant dean of the GSAS and director of the Graduate Writing Lab. In addition to these individual mentoring sessions, the Graduate Writing Lab offered a number of programs on presentation skills for the participants, including a series of workshops for developing oral communications skills and the Public Speaking Studio. Participants could use a software program in which they speak to a 3D-animated audience that reacts to their presentation. The software also provides instant personalized feedback on presentation delivery, from pacing to pitch to pausing, video replay, user-friendly analytics, and video tutorials. Kallestinova said the ability to succinctly explain your work is an extremely valuable skill.

“It’s not actually about presenting your dissertation in three minutes, but about being able to explain the essence and the most important parts about your research within a very short period of time,” she said. “It’s a skill, like an elevator pitch, and it can be used everywhere.”

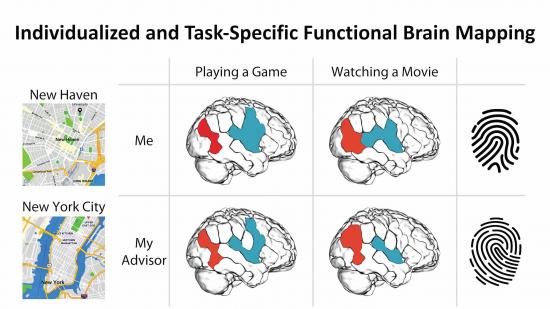

The work paid off, as Salehi took first place among the 14 competitors. With her one slide (shown here, to the right) and three minutes, she engaged the judges and audience in her research (conducted in the labs of her two advisors: Amin Karbasi, assistant professor of electrical engineering & computer science and Todd Constable, professor of radiology and biomedical imaging and of neurosurgery).

Focusing on creating brain maps that spell out not just the differences between people, but the differences in one person’s brain from one state of mind to another, the research could potentially lead to a better understanding of how the brain makes the transition from one emotional state to another and new treatments for depression. In addition to being a Ph.D. candidate in the labs of both Constable and Karbasi, Salehi is also part of the Yale Institute for Network Science (YINS).

Here’s an excerpt from Salehi's presentation:

“For my Ph.D. thesis, for the first time, I challenged my field’s long-standing assumption that there is a single brain map that works for everyone across time. I looked at brain images acquired by functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging or fMRI, and tried to understand what brain regions talk to each other and how this conversation changes as we engage in different tasks, such as playing a game or watching a movie. I developed an artificial intelligence technology to automatically translate these brain images into brain maps, like the ones you can see here. I applied this technology to brain images of 718 individuals and constructed their brain maps as they performed 8 different tasks.

“To my surprise, I observed that these brain maps are unique to each individual, such that I could uniquely identify people with 99% accuracy just by looking at their brain maps! The brain maps are like fingerprints! I also discovered that these brain maps are not fixed, but they reliably reconfigure by task, such that I could predict what people are doing, with up to 97% accuracy, just by looking at their brain maps!”