Harnessing the Sun to Disinfect Water

Poor access to safe drinking water is a major issue for a third of the world's population, especially for those living in rural areas. Because of the abundant sunlight in many of these regions, solar disinfection technology has great promise. It’s unclear, though, which form of solar disinfection would work best.

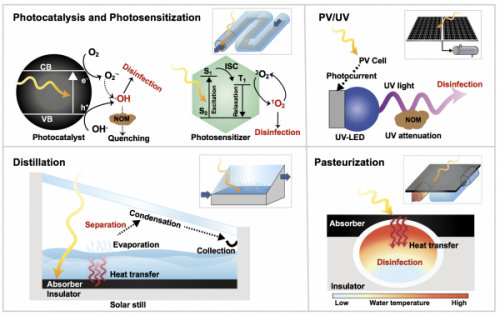

A team of researchers, led by Jaehong Kim, the Henry P. Becton Sr. Professor of Engineering at Department of Chemical & Environmental Engineering, has studied the pros and cons of five of the most common solar-based disinfection technologies that are applied at their point of use: semiconductor photocatalysis to produce hydroxyl radical, dye photosensitization to produce singlet oxygen, UV irradiation using LED powered by a photovoltaic panel, distillation using a solar still, and solar pasteurization by raising the bulk water temperature to 75 °C. The results are published in Nature Sustainability.

A team of researchers, led by Jaehong Kim, the Henry P. Becton Sr. Professor of Engineering at Department of Chemical & Environmental Engineering, has studied the pros and cons of five of the most common solar-based disinfection technologies that are applied at their point of use: semiconductor photocatalysis to produce hydroxyl radical, dye photosensitization to produce singlet oxygen, UV irradiation using LED powered by a photovoltaic panel, distillation using a solar still, and solar pasteurization by raising the bulk water temperature to 75 °C. The results are published in Nature Sustainability.

“It’s really the first analysis based on how much sunlight there is around the globe, and how we can utilize the sunlight for water disinfection,” Kim said. “Disinfection is the most important treatment goal in many cases because waterborne diseases are one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity around the globe.”

As part of their analysis, the researchers conclude that solar pasteurization may hold the most promise. It’s less dependent on breakthroughs in materials, less affected by the types of pathogens, and it achieves a much larger disinfection capacity on average.

“The reason it's effective is because every microorganism will die if the temperature is above 75 degrees Celsius for a few minutes,” Kim said. “Maybe it comes down to simply raising the temperature of the water - a simple but effective solution.”

Comparing the different methods can be tricky, Kim said, since conditions vary significantly around the globe - these include pathogen type, solar intensity, and water quality.

“We decided to do a holistic view in our approach to this problem by doing testing simulation, so this whole paper is based on computer simulations,” he said. “We did extensive sensitivity analysis and changed the variables to see how the performance depends on variations of certain parameters.”

The researchers focused on point-of-use technologies since many of the regions they studied have a very poor infrastructure and are off the grid. As a result, centralized water treatment and distribution is not a viable solution due to the high investment and maintenance costs involved. Point-of-use water treatment technologies, though, have relatively low costs and are simple to operate.

The paper could potentially serve as a guide for other researchers in the field of solar water treatment.

“This paper for the first time critically compares technologies that people have been studying over the past many decades,” Kim said. “I’m hoping that it becomes an important reference and guideline for anyone studying and practicing solar disinfection for water treatment.”

Co-authors of the paper are Inhyeong Jeon and Eric C. Ryberg of Yale, and Pedro J. J. Alvarez of Rice University.