Engineering Better Waves For Surfers Everywhere

When we talk about waves on the SEAS website, it's usually something to do with spin waves or wave particles. Today, we talk about actual waves, as in the kind used for surfing. And what better time to talk about surfing than on the first day of fall?

The technology of surfing, for much of the sport’s history, has focused on better boards for riding the waves. In recent years, though, some forward-looking folks have focused instead on the waves themselves and have created what’s known as “surf parks” or “wave gardens.” Here, surfers can ride artificial waves inside giant pools.

It’s a trend that could potentially mean that the next generation of surfing phenoms will hone their chops on waves from landlocked states - and the cold of autumn and winter months won't scare away the less dedicated. The current technology, while promising, isn’t quite there yet. A number of surf parks have been built in recent years, and all have their pros and cons. They tend to lack the variety of waves that surfers seek, and they don’t accommodate large numbers of surfers.

It’s a trend that could potentially mean that the next generation of surfing phenoms will hone their chops on waves from landlocked states - and the cold of autumn and winter months won't scare away the less dedicated. The current technology, while promising, isn’t quite there yet. A number of surf parks have been built in recent years, and all have their pros and cons. They tend to lack the variety of waves that surfers seek, and they don’t accommodate large numbers of surfers.

For the course Mechanical Engineering Special Projects (MENG 472), Jan Schroers, Professor of mechanical engineering, and Larry Wilen, a Center for Engineering Innovation & Design mentor and senior research scientist, set up the challenge of building a prototype of a surf park that would allow for the study of wave formation and to assess energy and economic requirements of an actual park.

Although no surfer herself, Katherine Berry ’17, took on the challenge. She built a prototype with help from Schroers and Wilen with the goal of designing a ring-shaped surf park that would produce longer-running waves.

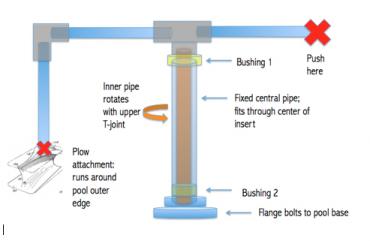

Her prototype is a 3-foot-by-3-foot-by-6-inch park base with a series of interchangeable underwater inserts, both made with polystyrene foam. A rotating arm made from PVC piping hangs overhead, pulling a small plow through the water to generate the waves. The base of the park is adjustable to produce a variety of wave sizes and shapes.

This fall, Berry moves on to other things, though other students may take up the project. A lot of progress was made in the spring, she said, but more work is needed on getting the waves to break. She’s hopeful that using a curved plow instead of the flat one of the current design would help correct this.

The sport of surfing goes back at least to the 18th century (as described by those on the third voyage of Captain James Cook to the Hawaiian Islands). In the 1960s, it exploded in the U.S., and became a pop culture phenomenon. Even so, you still need a coast if you want to surf – something that’s has kept surfing a niche sport. But a better-designed surf park could mean broader participation and greater visibility for the sport. It could even lead to its entry as an Olympics sport, something that the surfing community has long pushed for.

Berry said the project was a good way to demonstrate the far-reaching impacts engineering can have.

“It forced me to think about specialized needs for groups I am unfamiliar with inside a community, why those needs exist, and how to approach satisfying them without necessarily having a vested interest,” she said. “I think as an engineer it's good to be exposed to unfamiliar projects, because throughout your career you'll need to know how to ask the right questions to effectively and think through all kinds of diverse design problems that apply to groups beyond yourself.”