A Close Look at Forest Fire Smoke Yields New Clues About Air Pollution

With samples taken from an airplane and given an unprecedented level of offline analysis, Yale researchers have produced a highly detailed look at the chemical make-up and transformations of an evolving plume of forest fire smoke - findings that could contribute to a better understanding of air pollution in many parts of the world.

A team of researchers in the lab of Drew Gentner, associate professor of chemical & environmental engineering, performed a highly detailed analysis of an evolving smoke plume from a forest fire. The results show clear evidence for the formation of particle-phase organic compounds containing oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur – relatively little prior work has been done on the structure, formation, and impacts of these compounds. They also found that certain structural features that were part of these compounds increased significantly as the smoke plume evolved over a period of four hours. The study, led by Dr. Jenna Ditto, a former PhD student in the Gentner lab, is published today in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

A team of researchers in the lab of Drew Gentner, associate professor of chemical & environmental engineering, performed a highly detailed analysis of an evolving smoke plume from a forest fire. The results show clear evidence for the formation of particle-phase organic compounds containing oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur – relatively little prior work has been done on the structure, formation, and impacts of these compounds. They also found that certain structural features that were part of these compounds increased significantly as the smoke plume evolved over a period of four hours. The study, led by Dr. Jenna Ditto, a former PhD student in the Gentner lab, is published today in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

Previous studies have used mass spectrometry to study wildfire smoke. However, they have not fully captured these complex compounds and their chemical transformations in these smoke plumes. The Gentner lab used a unique approach of high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry for a more precise analysis of the evolving smoke plume, where target molecules are fragmented to examine their underlying structural features. This level of detail is an important step toward improving modeling capabilities and our understanding of the health and environmental impacts of biomass burning smoke.

Knowing the precise make-up of the smoke of these fires is particularly important, since experts predict that forest fires will become increasingly prevalent and severe due to climate change. The results from this wildfire-focused study chemical pathways are also relevant to places in developing regions or very large cities where residential biomass burning is common.

“It provides evidence for the formation of these understudied organic compounds with oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur that are likely to be relevant in other regions with substantial biomass and fossil fuel combustion, such as large cities in the developing world,” Gentner said. “Along with other researchers, we’ve seen significant amounts of these compounds at other field sites in the past, but often wonder about their formation pathways and underlying chemical structures, and this real-world biomass burning plume provided a great opportunity to study them.”

“It provides evidence for the formation of these understudied organic compounds with oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur that are likely to be relevant in other regions with substantial biomass and fossil fuel combustion, such as large cities in the developing world,” Gentner said. “Along with other researchers, we’ve seen significant amounts of these compounds at other field sites in the past, but often wonder about their formation pathways and underlying chemical structures, and this real-world biomass burning plume provided a great opportunity to study them.”

The study is part of an ongoing collaboration between Gentner’s lab with Environment & Climate Change Canada, the national environmental agency.

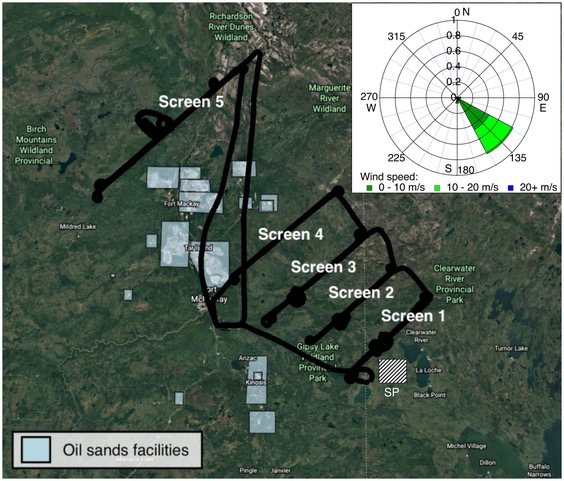

Samples were collected during two aircraft research flights by Environment & Climate Change Canada as part of its air pollution research program. These flights sampled two boreal forest wildfire smoke plumes that originated near Lac La Loche in northern Saskatchewan. The fire was a low-intensity surface fire with smoldering conditions. The particles were collected onto filters, placed in a deep freezer and sent to Gentner’s lab.