Yale History Blog

My research into the tenure of each Yale president -- there have been eighteen -- will look for policy decision and actions taken that affected the academic life on campus during their time. I search for decisions made as each president addressed their mission to educate the best intellects for service to church and civil state. Yale, like other elite educational institutions, must evolve to remain relevant and thus fulfill its mission for each generation. As mankind evolves, so must and so has Yale.

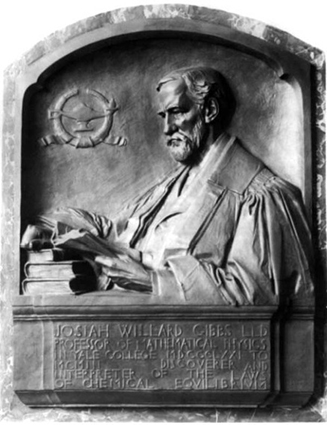

J. Willard Gibbs - Yale and Sheffield Scientific's Contributor to Theoretical Physics

Published July 14, 2014

Born on 1839, Willard was the fourth child of professor Joshua Willard Gibbs, a professor of linguistics and theology at Yale College. The Gibbs family produced distinguished theologians and academics for many generations. On his mother's side was Jonathan Dickinson, first president of Princeton, and on his father's side, Samuel Willard, who was acting president of Harvard in 1701 - the year Yale was founded. The Gibbs family of New Haven lived for many years on High Street near the center of the Yale campus.

Willard's father, known as Joshua, was instrumental in obtaining testimony from the Mendes survivors of a mutiny which had taken over the Spanish slave ship La Amistad in 1839. The ship was captured in the ocean off Long Island and the mutineers were put on trial in New Haven in 1841 to determine their legal status.

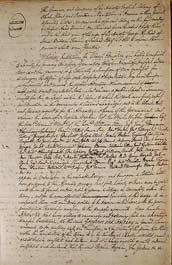

Because the Mendes spoke only their native African language, it was impossible for them to defend themselves. Gibbs, using his linguist skills, went to New York harbor hoping to find Mendes speakers among the visiting sailors. Finding two Mendes, he brought them to New Haven introducing them to the elated imprisoned captives. Gibbs learned enough of the Mendes' language to communicate with the prisoners and assist the attorneys tasked with their defense. Testimony from the 53 Mendes captives about their capture and voyage aboard the slave ship provided the judge and jury with the reality of their plight during the New Haven trial.

The senior Gibbs was an ardent abolitionist, and his aid to the Mendes survivors was critical to the defense in the New Haven case: United States vs. The Amistad which was appealed to the Supreme Court in Washington. The case was intensely followed in a divided country deeply concerned with the political reality of human slavery.

John Adams, former president, now elderly and well respected, eloquently defended the would-be slaves before the nation's highest court. He successfully won their freedom. Thus, with Joshua Gibbs help, 35 Mendes survivors returned to their homeland using funds provided by the United Missionary Society. A few of the Mendes chose to remain in the country as free people.

Joshua Willard Gibbs' son, known as Willard, graduated from the Hopkins school and entered Yale at 15 with the class of 1858. He was near the top of his class and, at his commencement, gave the salutatory address in Latin. After graduation, he stayed at Yale in the Sheffield Scientific School working to earn one of the first PhD degrees authorized by the Yale Corporation. Yale and the Sheffield Scientific School were the first American college to grant this advanced high academic degree. The Yale PhD degree was patterned after the technical schools of higher learning in France and Germany. No longer would students need to go to Europe to earn their PhD.

Joshua Willard Gibbs' son, known as Willard, graduated from the Hopkins school and entered Yale at 15 with the class of 1858. He was near the top of his class and, at his commencement, gave the salutatory address in Latin. After graduation, he stayed at Yale in the Sheffield Scientific School working to earn one of the first PhD degrees authorized by the Yale Corporation. Yale and the Sheffield Scientific School were the first American college to grant this advanced high academic degree. The Yale PhD degree was patterned after the technical schools of higher learning in France and Germany. No longer would students need to go to Europe to earn their PhD.

Willard's father had long been a member of the Connecticut Society of Arts and Sciences. Soon after he received his first Yale degree, Willard was inducted into this society which would prove most helpful in his later work in mathematics and physical science theory. In 1863, after years of study under Hubert Newton, he earned the fourth American PhD granted by Yale. His thesis was titled, "On the Forms of the Teeth and Wheels in Spur Gearing."

Remaining at Yale, he taught classes in Latin and Natural Philosophy in the Sheffield Scientific School.

When Josiah Gibbs died in March 1961, Willard and his sisters sat through a troubling funeral service in the College Chapel. Dr. Fisher, who gave the funeral oration, pointed out a fundamental of the senior Gibbs life: "Mr. Gibbs loved system... His essays on special topics are marked by the nicest logical arrangement. He would have done a greater service to the cause of learning. (if he had) the wider grasp, the power of more extended combination .... Through which multiform fragments of truth are organized and fused into a consistent whole."

To Willard, now the head of the Gibbs family and its rich tradition of service, these words were a ringing challenge. He was now destined to find answers to nature's most complex problems of heat and energy. His inheritance included substantial funds accumulated by his father's frugality and investment skills which allowed his son to travel extensively in Europe to learn from the top scientists of his time. Willard remained close to his sisters for the rest of his life, never marrying, but always receiving support and encouragement from the family group.

Gibbs inventive turn of mind was challenged by a braking problem faced by the rapid expansion of railroads. Mechanical brakes were affixed to each railroad car. As a train approached a station, brakemen ran through the cars applying brakes one at a time. Accidents often occurred when trains overshot the depot. Gibbs addressed this problem by inventing an air brake system which could activate all railroad car brakes at the same time. While he immediately applied for a patent it took many years for the patent to be issued whereupon the Westinghouse Company went into the manufacture of the Gibbs air-brake system which greatly improved railroad safety.

After receiving his doctorate, Gibbs was appointed tutor for three years, then, in 1867, he spent three years in Europe traveling with his sisters and meeting leading scientists, mathematicians, and physicists. He first attended advanced classes in mathematics at the Sorbonne in Paris, then went to Berlin University to study under other gifted mathematicians and scientists. He filled two notes books with the latest European opinions in many scientific subjects. He spent much time in Heidelberg attending lectures of Kirchhoff, Helmholtz, and Bunsen where he basked in the fascinating culture of new scientific inquiry.

In 1871, he returned to the Sheffield School as Professor of Mathematical Physics. Although he was a gifted lecturer who never used notes, his work was well above the average student's ability to understand his reasoning. Students were not the only intellects who had trouble following Gibbs writings filled with complex mathematical analyses and theories. Yet, he was a true gentle man, almost never critical or unhinged. His students recognized his mild demeanor understanding just enough to be impressed by a rigorous, organized, genius with a dedicated focus on understanding nature's complex world.

The work of a theoretical physicist is founded in a creative mind with a complete knowledge of mathematics who seeks to understand and explain the fundamentals of natural law. Thus, Willard Gibbs labored alone quietly writing his pages and making his convincing arguments often synthesized in simple equations. Correspondents included Clerk Maxwell at Cambridge, a leading scientist who understood the importance of Gibb's theories. Maxwell included a chapter of Gibbs' work in his 1875 publication "Theory of Heat."

The work of a theoretical physicist is founded in a creative mind with a complete knowledge of mathematics who seeks to understand and explain the fundamentals of natural law. Thus, Willard Gibbs labored alone quietly writing his pages and making his convincing arguments often synthesized in simple equations. Correspondents included Clerk Maxwell at Cambridge, a leading scientist who understood the importance of Gibb's theories. Maxwell included a chapter of Gibbs' work in his 1875 publication "Theory of Heat."

Gibbs finally determined to publish his basic work in thermodynamics and it was the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences who undertook publication. Lacking funds, the trustees took up a collection to print Gibb's "On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances." Part 1 was published in 1875 and Part 2 in 1878. In this publication, Gibbs stated the first and second laws of thermodynamics: The energy of the world is constant. The entropy of the world tends towards a maximum.

Muriel Rukeyser, Gibb's biographer, describes him as "one of those rare intellects which tower over art, over many kinds of conquest, as over science, from whom the human race receives its pictures of the world."

These principles launched the field of physical chemistry. After Gibb's "Great Paper" was translated into German and published abroad, German scientists became the founders of a great chemical industry that produced many useful products that benefited mankind.

In 1879, Gibbs spreading notoriety earned him a visit to Johns Hopkins to give a series of lectures on Theoretical Mechanics. All his years at Yale were served without pay - not uncommon at the time for a man of means. So, after the series of successful lectures ended, Johns Hopkins offered him a professorship with a$3000 per year stipend. When word got to the Yale campus, the thought of Gibbs leaving Yale caused a furor. The Corporation met and immediately offered him a $2000 yearly salary which pleased Gibbs and he remained faithful to Yale.

Also, in 1879, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In 1881, he received the Rumford Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Also, in 1879, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In 1881, he received the Rumford Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

From 1881 to 1884, Gibbs worked on vector analysis which he improved with a new system of notation that advanced and simplified this mathematical method. Honorary degrees began to be awarded and in 1901 he received the Copley Medal, the highest award of the Royal Society in England. He was awarded honorary doctor degrees from Princeton and Williams College plus many European honors for his work in physics, chemistry, and mathematics.

From 1881 to 1884, Gibbs worked on vector analysis which he improved with a new system of notation that advanced and simplified this mathematical method. Honorary degrees began to be awarded and in 1901 he received the Copley Medal, the highest award of the Royal Society in England. He was awarded honorary doctor degrees from Princeton and Williams College plus many European honors for his work in physics, chemistry, and mathematics.

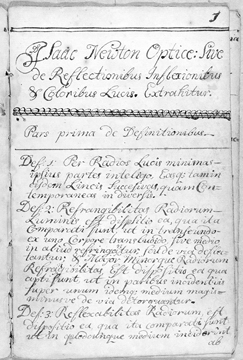

Willard Gibbs fundamental belief in simplicity and order created by a supreme being is similar to the beliefs of Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein. Gibbs, Newton, and Einstein all recognized the creative mechanisms of nature as the work of an almighty God. The order and functions they discovered in our universe reinforced their personal beliefs.

Einstein recognized the genius of Willard Gibbs when he said, " (Gibbs was) "the greatest mind in American history."

Einstein recognized the genius of Willard Gibbs when he said, " (Gibbs was) "the greatest mind in American history."

In 2005, the US Postal service held its first day of issue ceremony in Luce Hall on the Yale campus introducing commemorative stamps depicting "American Scientists." J. Willard Gibbs was the first of the series of four individuals which included John von Neumann, Barbara McClintock, and Richard Feynman. John Marburger, science advisor to the President, and Yale president Richard Levin adressed the attendees that included family members of the honorees. John W. Gibbs, a professor and distant cousin of Willard Gibbs also attended.

In 2005, the US Postal service held its first day of issue ceremony in Luce Hall on the Yale campus introducing commemorative stamps depicting "American Scientists." J. Willard Gibbs was the first of the series of four individuals which included John von Neumann, Barbara McClintock, and Richard Feynman. John Marburger, science advisor to the President, and Yale president Richard Levin adressed the attendees that included family members of the honorees. John W. Gibbs, a professor and distant cousin of Willard Gibbs also attended.

J. Willard Gibbs died in 1903 and is buried in the Gibb's family plot in New Haven's Grove Cemetery with his father and sisters.

Yale Engineering in the Post World War II Era

Published March 18, 2014

There is a surprising similarity between the Yale of the post war years following World War I and the post war years following World War II. In both instances, advances in military technology led to major changes in world order and the world economy during the peace-time decades following the end of the war. The challenge to universities, worldwide, was appropriate readjustment from a wartime environment to a peacetime community of higher education to prepare students to serve a global, peaceful world.

After WWI, the Yale administration moved aggressively to merge the Sheffield Scientific School with Yale College. The AC college emphasized liberal arts and traditional classical education while Sheff was the leading scientific-engineering school of its time. In 1919, a comprehensive study determined the most effective way to solve the duplication of courses offered by the two schools was to establish a mandatory freshman year for both AC and Sheff undergraduates.

After WWI, the Yale administration moved aggressively to merge the Sheffield Scientific School with Yale College. The AC college emphasized liberal arts and traditional classical education while Sheff was the leading scientific-engineering school of its time. In 1919, a comprehensive study determined the most effective way to solve the duplication of courses offered by the two schools was to establish a mandatory freshman year for both AC and Sheff undergraduates.

As a part of a comprehensive study of Yale curricula, the Sheffield governing board lost its ability to control the former autonomous and highly rated school of science and engineering leaving the Yale Corporation as the sole governing body. It took 13 years, until 1932, for Yale to reestablish a School of Engineering. The new school became a critical part of the change to a research university when Yale, Harvard, and other elite schools recognized the advantage of learning from research over the rote classroom learning taught in a classroom where teachers presented selected wisdom from the past.

In 1951, in the post WWII era, the retirement of Charles Seymour as president, brought a new, young president, A. Whitney Griswold, to face the challenge of change. What followed was a series of studies focused on reorganizing the then School of Engineering by add- ing the teaching of applied science and liberal arts courses to the engineering curricula allegedly to accommodate the post-war changing times.

In 1951, in the post WWII era, the retirement of Charles Seymour as president, brought a new, young president, A. Whitney Griswold, to face the challenge of change. What followed was a series of studies focused on reorganizing the then School of Engineering by add- ing the teaching of applied science and liberal arts courses to the engineering curricula allegedly to accommodate the post-war changing times.

Also, in 1951, Yale faced rebuilding a decaying campus. Maintenance of classrooms and laboratory buildings, deferred during the depression and war years, put a high priority on renovating old buildings and building new when necessary. Inflation raised costs so prompt action was needed. Faculty salaries - long fixed - needed a fresh look and Yale would need alumni largess to rebuild the campus and balance a growing budget. While the Yale endowment actually grew during World War II years, inflation and a down stock market reduced current income squeezing future budgets.

Also, in 1951, Yale faced rebuilding a decaying campus. Maintenance of classrooms and laboratory buildings, deferred during the depression and war years, put a high priority on renovating old buildings and building new when necessary. Inflation raised costs so prompt action was needed. Faculty salaries - long fixed - needed a fresh look and Yale would need alumni largess to rebuild the campus and balance a growing budget. While the Yale endowment actually grew during World War II years, inflation and a down stock market reduced current income squeezing future budgets.

Griswold followed Seymour’s practice of forming study committees to bring a fresh look and broader participation to solve problems. The long delayed need for a fund drive required organization and an appropriate campaign theme to raise vitally needed funds.

Whitney Griswold exuded a determined personality with set values that resounded long after his sudden death in 1963. He was a committed liberal arts enthusiast who treasured liberal arts education as Yale’s mandate. However, he also realized that Yale was deficient in the sciences when compared to Harvard and other leading institutions so rebuilding old Sheffield buildings and adding new became a second priority. The Kline Science Center, a new physics building, the Gibbs Laboratories, and the expansion of Dunham Laboratory were positive Griswold moves designed to return Yale to a leadership position in science and engineering.

The new president’s often stated view of Yale’s reliance on liberal arts put him in opposition to “service station” programs that he viewed as trade school training unworthy of a Yale degree. Concluding that the Yale School of Nursing was trending towards a vocational school, he demanded a new curriculum and turned the nursing school into a graduate school which accepted only students with a bachelor’s degree. This upset alumni and the faculty of the nursing school which had no choice but to adopt his changes.

The new president’s often stated view of Yale’s reliance on liberal arts put him in opposition to “service station” programs that he viewed as trade school training unworthy of a Yale degree. Concluding that the Yale School of Nursing was trending towards a vocational school, he demanded a new curriculum and turned the nursing school into a graduate school which accepted only students with a bachelor’s degree. This upset alumni and the faculty of the nursing school which had no choice but to adopt his changes.

Griswold also concluded that the Yale Department of Education was a normal school unworthy of a Yale degree. He insisted that the department become a graduate school with a new program, so the undergraduate program faded away.

In the fall of 1960, after little progress in his concept of a “new engineering program” despite two study groups, Griswold formed a a third committee headed by Professor Barnett F. Dodge. Dodge was a notable chemical engineering professor who had been president of the American Society of Chemical Engineers. Dodge was nearing the end of his career, however, he delayed his Yale retirement to head the latest high level engineering study committee.

The report of this committee, “The study of Engineering Education at Yale University” was submitted to Griswold in October 1961. Despite unanimous support from the president and the Corporation and much positive reaction, confusion in the various engineering departments remained. An ongoing debate on the definition of scientist, applied scientist, and engineer split the science and engineering departments diverting them from their mission to build strong, attractive programs that would bring top students and superior faculty to Yale.

READ MORE ABOUT YALE ENGINEERING IN THE POST WORLD WAR II ERA»

How the Sheffield Scientific School Came to Be

Timothy Dwight IV, Benjamin Silliman, and Joseph Earl Sheffield bring the "New Education" to Yale

Published December 6, 2013 (Edited April 26, 2014)

In 1802, a new president,Timothy Dwight, acted to catch up with Harvard, Dartmouth, Princeton, and Pennsylvania who had established the first medical schools in the country. To lay the groundwork for a possible Yale Medical School, the first need was a professor of chemistry. So president Dwight approached one of his most gifted graduates, Benjamin Silliman, asking him to forsake a career in law, and accept the challenge to become Yale's first professor of chemistry.

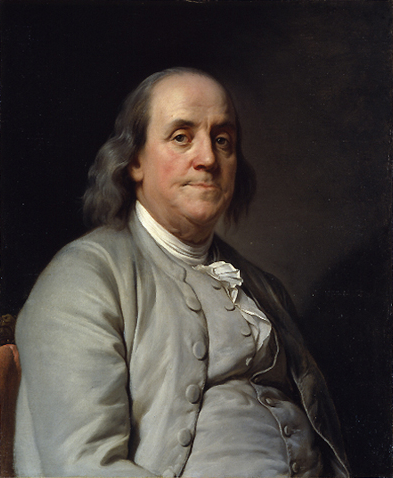

Silliman, eager to establish himself, accepted the challenge. He first spent a year in Philadelphia where Benjamin Franklin's legacy of science and Joseph Priestly's presence had created institutions to support the new country in the sciences of electricity, the new chemistry, and medicine.

Priestly, although near the end of his long life, had brought his discovery of soda water and theory of various "airs" (gasses) to the New Country. Priestly's isolation of oxygen is considered the turning point in refocusing the science of chemistry as distinct from and superior to the older alchemy and its magic theories. Silliman met Priestly and quickly added new, current knowledge in his quest to understand the chemistry advance theories that he would need to teach chemistry at Yale.

After two years of study in Philadelphia, Silliman realizes that a trip to England and Scotland would be essential to his learning of the new sciences. In 1803, he persuades the Corporation to appropriate funds for apparatus, books, and his travel expenses for a very successful tour of the science centers of England.

He returns to New Haven in 1804 prepared for a life long journey that would build Yale and New Haven into a center of "new education." Silliman's contributions went beyond chemistry to include geology, mineralogy, and medicine -- fields of strength for Yale that underpin the present schools which are among the best in the higher educational world.

In 1806, President Dwight induces an established physician, surgeon, and educator at Dartmouth - Nathan Smith - to become Yale's professor of medicine. This necessary step helps Silliman in his task to include the Connecticut Medical Society as they prepare a constitution for a new medical school at Yale. With Silliman's leadership, in 1807, the joint committee begins its deliberations and, in 1810, the committee submits a proposed constitution to the Connecticut General Assembly. The legislature gives its approval and the Yale Medical Institution is established.

In 1834, Silliman began an extensive series of public lectures traveling about the new country. One commentator remarked about his geology lecture, " He was perfectly at home among the wreck and ruins of a former world, balancing a flood of waters and a lake of fire. He stands, like some kind but mighty spirit sent to instill into the minds of the rising generation the sublime and awful mysteries of the past creation, himself 'filled to bursting nigh' with the majesty and grandeur of the subject."

Benjamin Silliman taught very popular and leading edge courses in geology, chemistry, and pharmacology. Students were choosing Yale over other institutions because New Haven had become a center of scientific learning. The Yale Corporation supported the "New Education" which was taught at a high level in the Yale schools of medicine, nursing, science, and engineering. All schools were expected to be financially self supporting.

Benjamin Silliman taught very popular and leading edge courses in geology, chemistry, and pharmacology. Students were choosing Yale over other institutions because New Haven had become a center of scientific learning. The Yale Corporation supported the "New Education" which was taught at a high level in the Yale schools of medicine, nursing, science, and engineering. All schools were expected to be financially self supporting.

In 1840, Silliman was asked by John A. Lowell to give the first public lecture at the new Lowell Institute in Boston which he had endowed with $250,000 to offer the people of New England, "Free lectures in science, literature and the arts." Silliman was introduced by Massachusetts Governor Everett as the leading scientist of his time. He continued to give regular lectures in Boston for four years. After his last lecture in 1843, he was named president of the American Association of Geologists and Naturalists, the predecessor of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Yale was again following Harvard who had established an advanced school of Science and Literature in 1846. This school, endowed by Abbott Lawrence, is named the Lawrence Scientific School in the University at Cambridge. Both the school at Harvard and the embryo school at Yale were, essentially, graduate schools which accepted students who had some college education elsewhere. New students in New Haven and Cambridge sought the latest education in science and technology to satisfy a growing need of the Industrial Revolution as it impacted the U.S. economy.

The Yale Corporation appointed John Pitcairn Norton as Professor of agricultural chemistry and Benjamin Silliman, Jr. as professor of practical chemistry in 1846. This decision established a separate science department at Yale. In the resolution there is a stipulation that no charges to the university are expected. Norton and assistant professor Benjamin Silliman, Jr. constructed a chemical laboratory in Farnum Hall. The Corporation decides, in 1847, then expands the scope of teaching into a Department of Philosophy and the Arts on a par with the departments of theology, medicine, and law. 1847 is the generally accepted birth date of a school of science at Yale.

The energy and ability of Norton succeeds in attracting many students and his proposal to the Corporation for granting a degree of Bachelor of Philosophy in chemistry in 1852 is accepted.

When J. P. Norton dies young at 40, the chemistry laboratory is taken over by John A. Porter who comes to Yale from Brown. (Silliman, Jr. accepts a post at the medical school of Louisville and leaves Yale.)

William A. Norton, is a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, then professor of mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Delaware College for eleven years, and now, in 1852, he is professor of civil engineering at Brown University. But Norton is unhappy with the Brown administration and their refusal to support his program. He offers to move his students and himself to New Haven which John Porter enthusiastically supports. The Corporation agrees providing the school is self supporting.

Little change takes place for two years as Porter continues his work in chemistry and Norton accustoms his engineering students to New Haven and Yale. In 1854, the two departments are combined as the Yale Scientific School.

In 1855, Benjamin Silliman, Senior, moves to professor emeritus as James Dana assumes his duties as professor of natural history and also teaches a course in mineralogy and geology in the Yale Scientific School. Benjamin Silliman, Jr. returns to Yale. An important addition to the faculty is George J. Brush, a graduate of the Yale Scientific School class of 1852, who is now promoted to professor of metallurgy.

In 1856, James Dana returns from a geological expedition in the Pacific Ocean and at the Yale Commencement exercises, he argues for a more formal and well financed structure for the Yale Scientific School.

Dana repeats his arguments before a Yale alumni group in New York City and this is followed by a brochure signed by President Woolsey, Benjamin Silliman (Jr. & Sr.), James Dana, John Porter, and George Brush which enumerates the needs and advantages of an expanded school.

Yale finds its benefactor in Joseph Earl Sheffield.

Joseph Earl Sheffield, born in Southport, CT in 1793, is the son of a ship builder and trader who sailed a privateer against the British in the War of Independence. In 1807, the fourteen year old Sheffield goes south to seek his fortune as an apprentice in a drug store in Newbern, NC. The South was a land of opportunity with cotton farming powering economic expansion which offered able businessmen the chance to prosper.

Joseph Earl Sheffield, born in Southport, CT in 1793, is the son of a ship builder and trader who sailed a privateer against the British in the War of Independence. In 1807, the fourteen year old Sheffield goes south to seek his fortune as an apprentice in a drug store in Newbern, NC. The South was a land of opportunity with cotton farming powering economic expansion which offered able businessmen the chance to prosper.

During the war of 1812, Sheffield, now with a trading house, twice successfully runs the British naval blockade of New York City at considerable profit. These successes are recognized by his superiors who promote him to full partner.

The end of the war in 1815 sees a decline in commodity prices which encourages Sheffield to move further south to the new port of Mobile, Alabama. He establishes trading routes between Mobile and New York City, Liverpool, and Le Havre. Sheffield remains in Mobile for 22 years building up his freight forwarding business in cotton and other in-demand southern goods.

In 1835, the "sickly climate" of Mobile proves unhealthy for Sheffield's wife. His concern for her health plus his abhorrence for slavery, impairs his ability to function in the South. These concerns are factors that encourage him to return to the northeast. He first spends summers in New Haven to escape the unhealthiness of a Mobile summer. His choice of New Haven for the next phase of his life was fortuitous for both the city and Yale College.

Sheffield accumulates sizable wealth though honest dealings and careful trading decisions. He builds a respected international reputation by adhering to ethical principles. As an eminent man of business, according to Yale President Noah Porter, "He was honorable from the convictions of his conscience and the sentiments of his heart."

Upon arriving in New Haven in 1835, Sheffield invests in the Farmington Canal which connects New Haven to Farmington, CT with plans to extend to Northampton, MA. When railroads replace canals as trade highways, Sheffield and his business partner, Henry Farnum, add a railroad line to the canal right-of-way.

Always looking for new business opportunities, Sheffield purchases the railroad rights-of-way between New Haven and New York City believing this would benefit New Haven and adjacent communities. When this investment proves successful, he moves west purchasing an essential right-of-way to connect New York City to Chicago. This enormously successful venture doubles the value of Chicago real estate. Sheffield follows with the creation of the Rock Island Railway and then builds a key bridge across the Mississippi River to open rail lines into the western interior of the country.

As Sheffield ages, he increasingly uses his wealth for good purposes. In 1855, his first donation to Yale was to Professor John Porter (his son-in-law) for a professorship in Analytical and Agricultural chemistry. Thereafter, Sheffield supports the "New Education" at Yale with "an unremitting flow" dedicated to technical and scientific fields.

In response to the first appeal for financial help on behalf of the Yale Scientific School, Sheffield purchases an old medical college building on the Yale campus near the Grove Street Cemetery. He enlarges the building and refits it before donating it to Yale as Sheffield Hall in 1860. In appreciation of Sheffield's continuous support, the Yale Corporation, in 1861 renames the Yale Scientific School, the Sheffield Scientific School despite Sheffield's personal reluctance for any sign of personal aggrandizement.

In 1866, the State of Connecticut grants $135,000 to the Sheffield Scientific School which encourages Sheffield to enlarge Sheffield Hall and donate $10,000 for a library. In 1871, Sheffield gives land and money for a second scientific building, North Sheffield Hall. His contributions to Yale continue and total about one million dollars - the largest private donations to the college up to that time. He never asks for special control or puts limitations on his donations -- always expressing full confidence in the Yale officials who receive his gifts.

After his death in 1881, his remaining estate is divided between the Sheffield Scientific School and his children. His wife completes the family donations when she bequeathes her Sheffield Hillhouse mansion to Yale.

In addition to his contributions to Yale, Sheffield supported Trinity College - as a trustee and benefactor - and, also, the Berkeley Divinity School then located in Middletown, CT.

Sheffield had a life long sympathy for the aged and disadvantaged - almost never turning away a beggar's hand. According to President Porter, "He provided first a hospital for the aged, a school of charity for the young, a church for the poor, and a great school of science and culture which widened and enhanced the reputation of the college and of the city itself."

President Porter observed, "Mr. Sheffield began his benefactions from a personal conviction of the value and promise of a tentative school which was then regarded only as an offshoot of a great university. It grew in his esteem and confidence as he witnessed its well-earned success by honorable methods, on a basis of honest work."

"Mr. Sheffield set the highest value upon a liberal education to develop and mature the student, and for this reason he supported schools of learning with such lavish liberality. He may, in some respects, have builded more wisely than he knew, but it was altogether in harmony with his judgment that the school which bears his name, early became more than a school of special skill and limited research and was lifted up with a college of liberal culture which aims as specifically to discipline the intellect and character as it does to impact technical knowledge and skill."

"Mr. Sheffield set the highest value upon a liberal education to develop and mature the student, and for this reason he supported schools of learning with such lavish liberality. He may, in some respects, have builded more wisely than he knew, but it was altogether in harmony with his judgment that the school which bears his name, early became more than a school of special skill and limited research and was lifted up with a college of liberal culture which aims as specifically to discipline the intellect and character as it does to impact technical knowledge and skill."

We remain forever in James Earl Sheffield's debt for his foresight and munificence in creating a lasting spring of knowledge that benefits Yale and the world.

Our indebtedness also must acknowledge the foresight of President Timothy Dwight who detected the absolute need to be in the leadership of the awakening of the science of chemistry and its ramification for the advance of medicine and other fields of scientific inquiry.

The willingness of Benjamin Silliman's son to follow his father's career also greatly contributed to the reputation of the Yale Sheffield Scientific School. Benjamin Silliman Jr. was a key contributor to the world's first oil boom when he determined that Pennsylvania "rock oil" had many useful applications. The US quickly became the world leader in the global oil industry.

Benjamin Silliman

The Yale Science & Engineering Association, is one of Yale’s oldest alumni organizations. Founded in 1914 as the Yale Engineering Association, science alumni were added in 1971. The YSEA will celebrate its centennial anniversary in 2014 with various projects including an updated history of Yale science and engineering containing this profile of Benjamin Silliman.

After his appointment as professor of chemistry in 1804, Silliman expanded his studies and teaching into geology, mineralogy, medicine, pharmacology, astronomy, and engineering. Silliman helped New Haven and Yale become the scientific center of the young United States. He contributed to the formation of the Yale Medical Institution in 1813. The geology department, and publication of the American Journal of Science in 1818 were his creations. He became an apostle of science spreading his knowledge by lectures, text books, and associations. Near the end of his life, he was a founder of the Yale Scientific School.

Published February 19, 2013

At the height of the War for Independence in April 1777, British ships attacked south of Fairfield, Connecticut launching an inland raid to destroy colonial military supplies in Danbury. Gold Seleck Silliman, father of Benjamin Silliman and general in charge of troops tasked to defend Connecticut and southeastern New York State, responded by harassing the British professional army.

In May, 1779, in the dead of night, Torrey raiders from Long Island, assisted by Fairfield loyalists, captured Seleck Silliman and his son, William, spiriting them across the Sound to Long Island where they were held prisoners for a year.

Mary Silliman, fearing that the capture of her husband was prelude to an attack on Fairfield, fled inland to Trumbull, CT where she gave birth to her second son, Benjamin. In July 1779 the British did return to burn the town of Fairfield.

The first Silliman to immigrate to Fairfield was Daniel Silliman -- a religious refugee whose ancestors came from northern Italy. Daniel moved to Holland with other dissidents who eventually sought asylum in the new world. He settled on a hill in Fairfield, built a large house with views of the Long Island Sound which is known as Holland Hill.

Benjamin’s father and grandfather both graduated from Yale College and both were lawyers. Grandfather Daniel was a Connecticut Supreme Court justice and his father, Seleck, became an effective general in the revolutionary army.

Silliman's student years

Benjamin Silliman entered Yale at thirteen, graduating near the top of his class in 1796. After graduation, following the family tradition, he studied law before returning to Yale as a tutor in 1799. In 1802, Yale president Timothy Dwight was bent on advancing Yale studies into secular areas. Harvard, Dartmouth, Princeton, and Penn had professors of chemistry and these colleges formed departments or schools for medical education.

Benjamin Silliman entered Yale at thirteen, graduating near the top of his class in 1796. After graduation, following the family tradition, he studied law before returning to Yale as a tutor in 1799. In 1802, Yale president Timothy Dwight was bent on advancing Yale studies into secular areas. Harvard, Dartmouth, Princeton, and Penn had professors of chemistry and these colleges formed departments or schools for medical education.

Dwight asked Silliman to forego becoming a lawyer - there was a surplus of practitioners in Connecticut - and learn all he could about the new science of chemistry. If he was willing, he would be appointed Yale’s first professor of chemistry. Dwight’s persuasive argument was, “Our country, as regards the physical sciences, is rich in unexplored treasures, and by aiding in their development, you will perform an important service and connect your name with the rising reputation of our native land.”

Yale at the turn of the century

The start of the 19th century was an exciting time for the new United States. The country grew rapidly and, the consensus among forward thinkers, was that rich natural resources and unexplored lands offered rare prospects. Growing cities and unexplored mineral riches would create new opportunities. The Age of Enlightenment expanded man’s vision as scientific learning and new inventions offered longer life and better living conditions to millions of people.

When Yale residential colleges were built in 1933, both Timothy Dwight and Benjamin Silliman were chosen as Yale legends worthy of a college name. These colleges are forever linked abutting each other on the site of the Sheffield Scientific School southeast of Grove Cemetery.

President Dwight realized that Yale must lead in secular areas and a chemistry course was necessary to keep pace or outpace Harvard and others. Yale must act and Dwight chose Benjamin Silliman for his outstanding scholarship, his good pedigree, and his total commitment to Yale. Dwight argument that there were many lawyers in Connecticut, but no accomplished chemists was persuasive. By accepting this challenge, Silliman would become Yale’s first professor of chemistry and his success would reward him handsomely as he helped the new country grow and prosper by applying the scientific principles he taught.

Benjamin Silliman's great challenge

Silliman first studied in Philadelphia in 1802 with the country’s leading chemistry professor, James Woodhouse, of the Medical School of Philadelphia. He was diligent in attending Woodhouse’s lectures and he met the famous Joseph Priestley, the discoverer of oxygen and a pioneer in chemistry. He became a close friend of Robert Hare, son of a wealthy brewer, who built a laboratory in their rooming house basement where they conducted their own experiments.

In 1803, Silliman spent a second winter in Philadelphia detouring to meet professor John Maclean, a Scotsman and chemistry professor at Princeton. In reflecting in later years, Silliman traces his approach to teaching chemistry to his interaction with Maclean who opened his laboratory and library to him with wit and brilliance.

In April, 1804, Silliman gave his first lecture at Yale on chemistry to the senior class using his accumulated apparatus and chemicals to illustrate various phenomena. Thus began a fifty-six year career as professor and expert in the new science of chemistry. In a short time, he raised Yale College to be a leading source of knowledge in a western world-- not only in chemistry -- but also in geology, mineralogy, astronomy, and medicine.

Silliman’s first European adventure

Silliman realized that the seat of new learning in the developing sciences was in Europe, particularly England and France. With the support of the Yale Corporation and a financial stipend of $9,000, in 1805, Silliman carefully planned his trip to Europe. Before leaving, he spent time in New York City with Benjamin Perkins who had accumulated a small “cabinet” of rock specimens. Perkins gave him letters of introductions to numerous scientific leaders in England. Thus began, Silliman’s introduction into the emerging science of geology.

Silliman sailed to Europe intent on increasing his proficiency in chemistry while also purchasing books and chemical apparatus for Yale. He would expand his knowledge by contact with many leaders in the natural sciences including medicine. His success, as chemistry professor, would establish Yale as a center of scientific knowledge in the new world.

Using his letters of introduction to English, Scottish, and European intellectual leaders and natural scientists, he became friends and correspondent with many leading European scientists. Through letters and personal meetings, he became conversant with the latest European discoveries and newest scientific theories. He increased his personal knowledge base to prepare courses and lectures that he effectively presented to Yale students and the general public.

In Edinburgh, he learned of conflicting theories of the earth’s formation and evolution. A. G. Werner of Freiburg, Germany, eloquently proposed a theory of geology based on two great floods, as described in the Bible. Werner saw these massive oceans as the mechanism of the earth’s rock crust formation. James Hutton, a Scotsman, disputed Werner’s claim that the earth was quite young - perhaps 5000 years old. Hutton saw evidence of a most ancient world that continued to evolve from fire beneath the surface. Fascination with rocks and the new science of geology stimulated Silliman to collect rocks to illustrate his lectures on the composition of the earth’s crust. Silliman expanded his knowledge beyond chemistry to include the new fields of geology and mineralogy.

Expanding his science studies, Silliman attended lectures at Edinburgh University in medicine, materia medica (pharmacology), anatomy, and mineralogy. He read Scottish science journals which later encouraged him to form the American Journal of Science.

An invigorated Silliman returns to Yale

Silliman returned to New Haven and Yale College in June 1806 with chemical apparatus, a science library, copious notes of his interviews, a travel journal, and a meticulous record of all expenses. The Corporation accepted his return with appreciation and approved his expenses with thanks.

He quickly resumed his work as professor of chemistry preparing a series of well-attended lectures to which he added geology. With the cooperation of the Corporation and president Dwight, he oversaw the building of a chemical laboratory and lecture hall.

When Silliman noted similarities between East and West Rock in New Haven and Salisbury Craig, a cliff near Edinburgh, he hiked the nearby cliffs accumulating rocks to compare them with those found in Scotland. This geological study in mineralogy resulted in a well received presentation to the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences in September 1806.

On vacation in Providence, RI to visit his brother, Selleck, he was introduced to Colonel George Gibbs who had amassed a large collection of European rocks. Silliman was fascinated by the size and great variety which Gibbs had in storage in a Newport warehouse.

Yale explores founding a Medical Institution

In 1806, President Dwight presented a resolution to the Corporation for a new appointment -- professor of medicine. A special committee -- President Dwight, Benjamin Silliman and Nathan Strong -- was appointed to explore the creation of a Yale Medical Institution. Because the State of Connecticut had a powerful Medical Society which licensed doctors, the college committee needed a harmonious relationship with them. Silliman was an effective negotiator who found common interests between Yale’s ideas for a medical school and the Societies commitment to quality medicine. In the autumn of 1807, the joint committee produced a constitution for a medical institution at Yale that satisfied both the College and the Medical Society.

In October 1807, Silliman began lectures in chemistry and added lectures on the contemporary sciences of the time. To support his lectures in chemistry, he published an American edition of Henry’s, “An Epitome of Chemistry” complete with his own notes now adapting the text to his chemistry lectures.

His students had little concept of scientific learning as their Yale education was primarily classical and ecclesiastical. Silliman evolved a practical style with boyish enthusiasm and many experiments. When teaching chemistry, he often diverted to geology to emphasize a point. His rock collection spiked interest in geology and he is credited as the first to lecture on the new field of geology in America. His reputation as an accomplished, enthusiastic teacher grew as his classes became popular and effective.

Yale becomes a geology center

Silliman expanded his small European rock collection adding rocks from New England. He bought Benjamin Perkins’ rock collection for $1000. He resumed his contacts with Colonel Gibbs in Rhode Island and he traveled to Boston to see what was new at Harvard. He concluded that, “there was not much spirit of science in Boston.”

With his expanded Yale collection as a useful display, Silliman offered Yale’s first course in mineralogy. Students paid a small ticket price for the course which became very popular. With this success, Silliman introduced the concept of elective courses to Yale.

1807 was a special year for Silliman as December brought the Weston Meteor which lit up the sky from Canada to Connecticut. Now, his interest in astronomy interfaced with his knowledge of chemistry. Silliman bought fragments of the meteor from a farmer in Weston and performed a quantitative chemical analysis of its contents. At that time, the source of meteors was unknown. Theories abounded that they could be chunks of earth, parts of the moon, or particles from outer space. His chemical analysis was published by the American Philosophical Society and science societies in England and France. Silliman was now notable as a general scientist willing to explore all areas of human knowledge.

In 1808, Silliman’s notoriety and his recognized excellence as a science expert brought a suggestion from President Dwight that he modify his basic chemistry lecture for presentation to the general public. Silliman responded positively and invited Harriet Trumbull (daughter of the governor) to his first New Haven public lecture.

In 1808, Silliman’s notoriety and his recognized excellence as a science expert brought a suggestion from President Dwight that he modify his basic chemistry lecture for presentation to the general public. Silliman responded positively and invited Harriet Trumbull (daughter of the governor) to his first New Haven public lecture.

Young men of his time needed a modicum of success before proposing marriage to a woman of the gentry. Silliman now could see a bright future: his success at Yale was established, his European travel journal was about to be published, and his report on the composition of the Weston meteor brought international recognition. A year later, Benjamin and Harriet were married and soon the young Sillimans built a substantial house on Hillhouse Avenue to accommodate a growing family.

Silliman ventures into business

In 1809 he partnered with Stephen Twining and other Yale friends to take advantage of a growing business prospect. His Philadelphia friend Priestly discovered that a popular spa at Pyrmont in England consisted of water impregnated with carbon dioxide. Silliman purchased equipment from Philadelphia which enabled him to make similar “soda water.”

The public demand for health giving “spa soda water” was exploding. While demand in Connecticut was limited, the fad was escalating in New York City. Silliman and partners competed intensely with Usher from Philadelphia. Both tried to build a profitable business by enticing New York Society into “soda fountains” to enjoy healthful benefits from man-made spa waters. Hope for a quick profit faded when the fad subsided and manufacturing problems arose. Silliman’s process used wooden casks specially made to hold the pressurized waters. Usher developed copper tanks which could withstand the high pressure while Silliman’s wooden casks leaked.

While business success in soda water faded, Silliman’s travel journal of his experiences in England, Scotland, and the Continent drew rave reviews from relatives and friends. Author’s had to finance the cost of book publishing, a cost that Silliman could not bear. When Daniel Wadsworth of Hartford, a man of means, asked to meet him, with suggestions on organizing the journal’s content and editing, Silliman responded positively. Wadsworth saw good market potential in England and America. Silliman and Wadsworth became close friends as they edited the manuscript for publication.

His growing reputation brought inquiries from investors who sought help in accessing the natural resources of the new country. His analysis of mineral and ore deposits provided an additional source of income. In 1810, his first commission -- a survey of a lead mine in Massachusetts -- earned him $50 in gold for his study and report.

The Yale Medical Institution is formed

In 1810, the Connecticut General Assembly approved an Act of Incorporation for the Yale Medical Institution. Yale now needed a course of study, facilities, and new professors and instructors. The school also would benefit by appointing a person of high repute to lead it. Dr. Nathan Smith, currently at Dartmouth, was the ideal choice: an experienced administrator, a renowned teacher, and recognized medical investigator.

At Commencement 1813, Dr. Smith was appointed Professor of Theory and Practice of Physic, Surgery, and Obstetrics along with Drs. Munson, and Ives of New Haven, and Benjamin Silliman, professor of Chemistry and Pharmacy, with Jonathan Knight as Professor of Anatomy. The Medical Institution opened in the fall with thirty-seven students.

The Gibbs Cabinet and Yale Geology

Silliman reconnected with Colonel Gibbs who was seeking an exhibit space for his extensive European rock collection at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point. No adequate space could be found. Gibbs was frustrated by lack of interest in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Gibbs asked Silliman for help in displaying his extensive collection in New Haven.

Silliman proposed to President Dwight that the second floor of South Middle College be renovated as a large display room for the Gibbs “Cabinet.” Dwight and the Corporation supported the project and Silliman, working with the college carpenter, designed and built glazed display shelves that attractively displayed the complete Gibbs collection.

The Gibbs cabinet became a powerful attraction for visitors to New Haven. The superb presentment of the rocks of Europe and other far off places made a dazzling display. Formal opening ceremonies were held on June 12, 1812, the very day that war was declared between the U.S. and Britain. Despite this distraction, the opening took place with many visitors and a well pleased Colonel Gibbs in attendance.

The War of 1812 was unpopular in New England. While the contentious point was freedom of the oceans and New England states were deeply involved in seafaring commerce, most northeast political leaders were fearful that an attack on Canada would bring reprisals by the British who would mount raids on their exposed seaports. At Yale, students mustered in military companies to protect New Haven. The memory of the British attack on New Haven in 1779 was fresh in mind.

President Timothy Dwight died in 1817. Silliman was asked to give the funeral oration and he also was a candidate to succeed Dwight as Yale president. However, the Corporation was not yet ready to break the succession of Congregational ministers who were Yale leaders from the beginning. Jeremiah Day, a close friend of Silliman, was appointed Dwight’s successor as Yale’s 9th president.

Founding the American Journal of Science

Silliman and other friends were contributors to Bruce’s American Mineralogical Journal, the first of its kind in the new country. When Archibald Bruce became ill in 1817, the annual issue was unlikely to be published. George Gibbs, at a chance meeting crossing the Sound, suggested that Silliman edit the next issue. Bruce willingly agreed and at the urging of another geologist and friend, Parker Cleaveland, Silliman responded positively. He corresponded with many of his other geology-minded friends and by 1818, he found a printer and enough subscribers to launch the American Journal of Science and Arts with a first printing of 500. Silliman broadened the scope of the journal beyond geology attempting to meet the high standards of European scientific journals.

The success of the Gibbs rock collection displayed at Yale, the publishing of Silliman’s travel journal, his popular lectures on chemistry together with his affiliation at the Yale Medical School raised Benjamin Silliman to a man of renown in the scientific world of his time. George Gibbs, now a close friend, proposed that he form an American Society of Mineralogy and Geology. Silliman, with Gibbs and Cleaveland supporting him, agreed. In May 1819, Silliman shepherded a charter, presented by Gibbs, through the Connecticut Assembly with he, Gibbs, Cleaveland, and other friends as directors. (This Journal is still published by the Yale Geology Department.)

Founding the Yale Art Gallery

For many years, Benjamin Silliman had known Colonel John Trumbull (formerly an aide to General George Washington) as his wife’s uncle. After the war in 1778, Trumbull went to England to study painting with Benjamin West. His eight historical paintings of the Revolutionary War had been duplicated “at great personal expense” in the hopes that the paintings and engravings would be widely popular. In 1830, Silliman met Trumbull, in his New York City apartment finding him despondent and in dire financial straits because of his lack of success in selling his Revolutionary War art. Trumbull was angered at the lack of patriotic ardor of the present generation. He now offered all his art (originals and engravings) to Yale for a life time annuity of $1000 per year.

For many years, Benjamin Silliman had known Colonel John Trumbull (formerly an aide to General George Washington) as his wife’s uncle. After the war in 1778, Trumbull went to England to study painting with Benjamin West. His eight historical paintings of the Revolutionary War had been duplicated “at great personal expense” in the hopes that the paintings and engravings would be widely popular. In 1830, Silliman met Trumbull, in his New York City apartment finding him despondent and in dire financial straits because of his lack of success in selling his Revolutionary War art. Trumbull was angered at the lack of patriotic ardor of the present generation. He now offered all his art (originals and engravings) to Yale for a life time annuity of $1000 per year.

Silliman, always ready to act on behalf of Yale and its reputation as a leading intellectual community, proposed to new president Jeremiah Day that Yale accept this offer. Day was enthusiastic. Trumbull then thought he might divide the collection between New Haven and Hartford, with Daniel Wadsworth, another close friend of Trumbull, as the proposed Hartford recipient. Silliman received pledges of support for Trumbull’s annual $1000 stipend from Day, Goodrich, Twining, and himself. Also Wadsworth accepted that the collection should stay together in New Haven, and he joined the other contributors to Trumbull’s maintenance.

To house the paintings, Silliman approached the Connecticut State Assembly for funds to erect a building on the Yale campus. With the support of two Yale alumni, who were also legislators, Truman Smith and Judge Romeo Lowry, the legislature approved $7000 for the building. Silliman oversaw the construction with the help of the Yale treasurer at a cost of $5000.

Colonel Trumbull helped select furnishings and guided the design of the “chastely classical” building. Trumbull brought all his paintings and engravings by packet ship from New York (the steamer company offered free passage). The grand opening for the Trumbull collection in the new and the first college art gallery in the country took place in October 1832. Benjamin Silliman was the first curator of the Yale Art Gallery. Jonathan Trumbull wished to be buried beneath the gallery, so upon his death in November 1843, Silliman, the executor of his will, “deposited his body in its last resting place.”

Benjamin Silliman as traveling lecturer and consultant

Over the next years, until his semi-retirement from teaching in 1833, Silliman displayed an exceptional skill at teaching chemistry, geology, mineralogy, and general science that encouraged students to choose careers in science.

For his own information, Silliman prepared a roster of assistants and pupils who became notable professors, lawyers, physicians, editors, and the founder of RPI (Ames Eaton.) This remarkable chronology of achievers helped elevate the young country to global recognition. Timothy Dwight’s prediction, in 1802, that Silliman could earn international repute by helping the young country become a bastion of new knowledge became reality.

In 1834, when Silliman began his long lasting series of public lectures traveling about the new country. One commenter remarked about his lecture on geology, “ He was perfectly at home among the wreck and ruins of a former world, balancing a flood of waters and a lake of fire. He stands, like some kind but mighty spirit sent to instill into the minds of the rising generation the sublime and awful mysteries of the past creation, himself ‘filled to bursting nigh’ with the majesty and grandeur of the subject.”

In 1840, Silliman was asked by John A. Lowell to give the first public lecture at the new Lowell Institute which he had endowed with $250,000 to offer the people of New England free lectures in “science, literature and the arts.” Silliman was introduced by Massachusetts Governor Everett as the leading scientist of his time and he continued to give regular lectures in Boston for four years. After his last lecture in 1843, he was named president of the American Association of Geologists and Naturalists, the predecessor of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

In 1846 President Day, after 30 years in office, resigned because of failing health. Again, Silliman’s name was put forward by friends as a worthy successor as president of Yale. Silliman correctly read the feelings of the Corporation. Yale had always had Congregational ministers as presidents and they were unlikely to change that tradition. Also, science was viewed as a threat to liberal arts by many professors. His outstanding success at bringing popular new sciences to Yale was not viewed unanimously as a good measure.

With some personal reservations, Professor Theodore Dwight Woolsey accepted the mantel of Yale president. Woolsey prime interest was in ecclesiastical research. He was content to leave his strong administrators as the forward movers of the college in their separate areas. Silliman continued his classes and public lectures on behalf of Yale science until his death on Thanksgiving Day 1864.

In 1849 he received an honorary membership in the Smithsonian Institute and in 1851 he gave two lectures in Washington.

Silliman was one of the first American mining consultants as “forward-looking men” sought professional advice on mineral deposits. In the 1830s and 1840s, he traveled widely, sometimes in dangerous territory, to evaluate potential valuable ores. He examined the coal-rich Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania, gold mines in Virginia, and iron ore deposits in Illinois. His last consultancy, in 1855, was in Virginia when he and Benjamin, Jr. investigated a vein of copper in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

In 1851, with six month leave granted from his college duties, he returned to Europe with his son Benjamin Silliman, Jr. and others. This time, travel was on the S.S. Baltic, a steam engine powered side wheeler mail boat that made the crossing in eleven days. He reconnected with his English correspondents as an old friend. He found Oxford well behind Yale in its knowledge of geography, chemistry, and sciences in general - still mired in the classical education of the past. In the French Academy, he found the true center of the European world of science and met many distinguished scientists, geologists, and physicians. Traveling to Italy, he climbed Mt. Vesuvius, saw Stromboli, and climbed part way up Mt. Etna marveling at these active volcanoes still forming the crust of the earth. Next he traveled through Switzerland to Berlin where he attended the Geographical Society. He visited Heidelberg and the School of Mines at Freiburg, home of Abraham Werner, the famous geologist whose theory of the earth’s creation was now supplanted as the new science of geology widely accepted Hutton’s theory of the earth’s formation.

Silliman’s suasions - Sheffield Scientific and the Peabody museum

Silliman attempted to retire in 1853, however, the Corporation granted him professor emeritus status and asked Silliman to continue his lectures in Mineralogy and Geology. Benjamin Silliman, Jr., his son, became Professor of General and Applied Chemistry with a joint assignment to the medical Institution - a position that Silliman had held from its inception in 1813.

Silliman’s protege and personal assistant, James Dwight Dana, who had come to Yale to study geology under Silliman’s tutelage in 1835, completed a brief study entitled, A System of Mineralogy. In book form, it was enthusiastically accepted as a seminal work of geology in both America and Europe. Dana then spent four years in the South Pacific studying the major islands of the Pacific Ocean. In 1844, he returned to New Haven and married Henrietta Silliman, Benjamin’s third daughter. In 1856, he took over most of the aging Silliman’s duties. In his introductory speech he lauded Silliman as the creator of the science of geology in America - an enviable position where Yale still maintains its international leadership.

In 1846, Silliman and his son Benjamin, Jr. created two additional chairs in science: agricultural chemistry and vegetable physiology. These courses would essentially be advanced courses or graduate studies. Yale was moving to become the first to offer advanced degrees. In 1847 the School of Applied Chemistry became the Department of Philosophy and the Arts which would eventually become the Yale Graduate School. The specific program proposed to the Corporation was for two new professors, but the underlying argument was a new venture in scientific education because the professors appointed had no undergraduate duties.

In 1846, Silliman and his son Benjamin, Jr. created two additional chairs in science: agricultural chemistry and vegetable physiology. These courses would essentially be advanced courses or graduate studies. Yale was moving to become the first to offer advanced degrees. In 1847 the School of Applied Chemistry became the Department of Philosophy and the Arts which would eventually become the Yale Graduate School. The specific program proposed to the Corporation was for two new professors, but the underlying argument was a new venture in scientific education because the professors appointed had no undergraduate duties.

In 1852, William Augustus Norton was named professor of civil engineering which is now considered the beginning of engineering at Yale.

In 1857, George Peabody came to Yale to visit his nephew Othniel Marsh, a sophomore in the class of 1859. Silliman met with Peabody suggesting he might be interested in supporting the new Yale Scientific School. Marsh became interested in the school taking post graduate courses. In 1863, Peabody donated $100,000 for the promotion of Natural Science at Yale selecting Benjamin Silliman as one of the trustees of his legacy.

The Silliman Legacy

Benjamin Silliman died on Thanksgiving Day, November 24, 1864 at the age of 85 years - a long illustrious life of service to God, Yale, and Country.

Benjamin Silliman died on Thanksgiving Day, November 24, 1864 at the age of 85 years - a long illustrious life of service to God, Yale, and Country.

He was an exemplary teacher of science, however, he spent little time in laboratory research. He used vials and flasks for experiments that would later demonstrate a chemical reaction in a lecture that entranced his students.

His expansive connections to men of science across the western world was useful and contributed to his knowledge of new theories and innovations. Scientific knowledge was moving forward, and the world would be forever changed as people craved the newest, the healthiest, and improvements at the crest of the industrial revolution wave.

He was an exceptional conciliator able to weld a strong Congregational creed to the open eyed acceptance of scientific fact. An all-knowing God was now enlightening mankind to the great mysterious of His universe. Werner and Hutton, geological theorists, were both correct (in part), so Silliman walked between the two to attract all. This was his style, his personality, his greatness to always seek common ground.

In an obituary published a few days after his demise, Daniel Gilman concluded, “Professor Silliman had the rare magnetic power of kindling enthusiasm and awakening cooperation of all whom he wished to reach. He was kind of heart, clear of head, sympathetic, courteous, sagacious, and enterprising that (earned him) affectionate admiration, unqualified respect, veneration, and gratitude (from) pupils and friends through the length and breadth of the land.”

Benjamin Silliman, Jr., was one of many scientists who became Silliman’s legatees. His son inherited his father’s professorship and the good will of many. Silliman, Jr.’s greatest achievement was his analysis of Pennsylvania “rock oil” concluding that it would be useful as an illuminant and lubricant. Based on his conclusions, the first oil boom in the world occurred in Oil City, Pennsylvania and the age of petroleum emerged.

The Sheffield School at Yale University became the leading United States source of scientific and engineering studies during the Industrial Age.

Acknowledgements

George P. Fisher, Life of Benjamin Silliman, New York, 1866

Fulton & Thomas, Silliman, NY, 1947

Chandos Michael Brown, Benjamin Silliman, Princeton Univrsity Press, 1989

B. M. Kelley, Yale, A History, Yale University Press, 1974

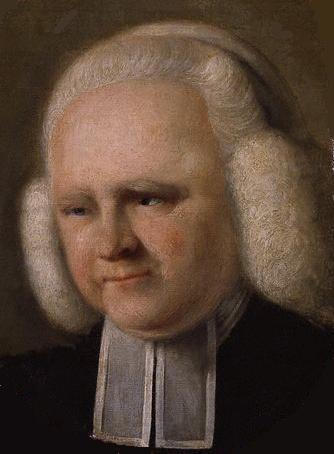

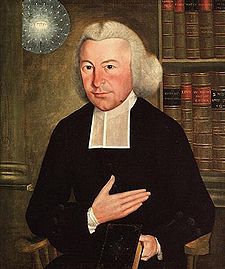

Ezra Stiles

The 8th President of Yale University

1778 to 1795

Published May 4, 2012

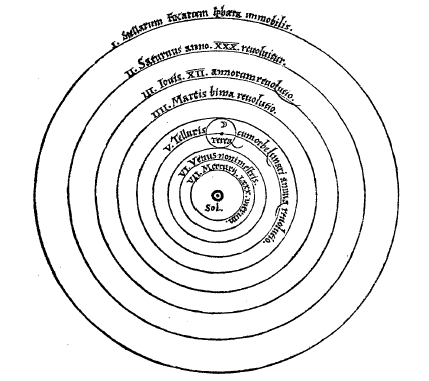

Ezra Stiles will become the center of a trio of presidents that create a university of world renown at Yale. Beginning with Thomas Clap’s creative expansion of Yale into secular Enlightenment courses in mathematics and natural philosophy, Yale would turn from a seminary for Congregational ministers to a seat of knowledge for secular education in science and the humanities. Stiles would expand language education both in English and in Hebrew. He would allow belle lettres and dramatics to flourish. He was energetic in adding courses in Newtonian physics and astronomy.

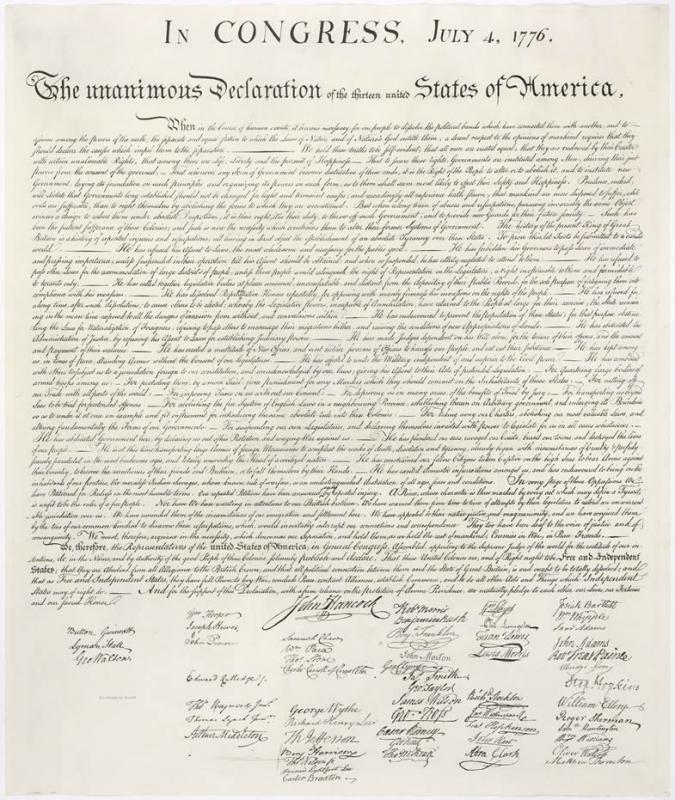

During the second half of the 18th century, Yale emerges under Clap, Stiles, and Dwight, as the premier school of higher education in the colonies produce strong intellectuals that implement the remarkable achievements of the Constitutional Congress of 1787. The United States of America becomes the world’s first government with a written republican constitution that successfully replace a monarchy.

During the second half of the 18th century, Yale emerges under Clap, Stiles, and Dwight, as the premier school of higher education in the colonies produce strong intellectuals that implement the remarkable achievements of the Constitutional Congress of 1787. The United States of America becomes the world’s first government with a written republican constitution that successfully replace a monarchy.

Ezra Stiles grandfather, John Stiles was among the first settlers of Windsor, CT. Ezra’s father, Isaac, after graduating from Yale in 1722, became minister of the North Haven Congregational Church and now lived on a 100 acre family farm.

Since his mother, Kezia Taylor, was daughter of a minister from Westfield, MA and because his father had a Yale degree, Ezra would learn Latin and Greek and look to Yale for his future education.

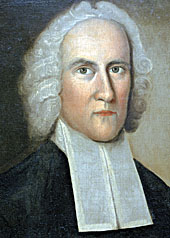

Stiles entered Yale at fifteen in 1742. The Great Awakening was then two years old and the Congregational Church in Connecticut was harassed and divided. Father Isaac Stiles joined Jonathan Edwards to offer alternatives to George Whitefield’s appealing call for repentance. After Whitefield left New England, Connecticut was assaulted by traveling evangelists who attacked Connecticut Congregational church leaders with questions about the validity of their ordinations. Ministers split into Old Lights, who were conservative Calvinists, and New Lights, who agreed with Whitefield, that the church needed radical change. Isaac Stiles, Jonathan Edwards, and Yale president Thomas Clap, emerged as leaders of the Old Lights.

Clap, in his 26 years of service as Yale president, engineered major changes in the Yale curriculum. He introduced required mathematics courses, advanced teaching of Natural Philosophy, (including lectures in astronomy and medicine), and he lectured on Common Law. Yale was transiting from a school designed to educate Congregational ministers to a broader curriculum that offered young intellectuals options that served a secular world. The rapidly growing colonies needed leaders in government, academics, law, and medicine. Ezra Stiles’ future, as Yale president, would be to change Yale from a Congregational seminary for intelligent youth to a university for educating leaders of a new country.

Ezra Stiles’ years at Yale as an undergraduate and tutor inflamed his curiosity for research in multiple areas. His tolerant disposition and impressive intellect earned him a reputation as an American intellectual. Unlike his father and unlike his mentor, President Thomas Clap, he avoided confrontations. He was a listener and correspondent who built close relations with numerous intellectuals in the colonies and in Europe. He believed in the effectiveness of associations and in ceremony and rituals. He suppressed a tendency to vanity. He was most pleased when Benjamin Franklin recommended him for an honorary doctorate from the University of Edinburgh which gave him a title - Doctor Stiles - which he treasured for the rest of his life.

Stiles’ years at Yale were lived with major background issues of religious turmoil and political unrest. Enlightenment beliefs contrasted with traditional teaching and new Yale graduates often challenged their superiors - particularly those bound by ancient traditions of learning. Stiles’ readings included George Berkeley and Isaac Newton whose views of our universe were contradictory. The lasting impact of his Yale education was development of an open mind willing to contemplate any well-reasoned argument. He tolerated well conflicting ideas and very seldom reacted with anger.

Ezra Stiles presented the class oration of 1746 on the subject: The king is not a divine authority. After graduation, Clap elevated Stiles to tutor and he spent the next 3 years earning his MA degree in 1749. He continued on as a popular tutor for another three years taking an interest in the law. He applied and received a license to preach - the usual first step for candidates seeking a Congregational church ministry. However, the ongoing split within the Connecticut churches gave him pause and he was reluctant to choose sides in a fractious debate.

In 1750, Ezra was invited to preach at Stockbridge, MA - a utopian community of Indians and colonials formed by the General Court of Massachusetts according to a plan of John Sergeant - a Congregational minister. Abigail Sergeant, John Sergeant’s attractive widow, was an intelligent leader of the community. Ezra, despite his infatuation with Abigail, turned down an offer to minister to this community believing he would be drawn into a destructive fight between Old Light and New Light Congregationalists. Ezra went back to work at Yale and to his apprenticeship in law.

His first visit to Newport, Rhode Island, in 1752 was for his health. He was a house guest of an Anglican college friend. The visit led to Ezra receiving an offer from the Anglican church of 200 pounds a year (five times his father’s salary) should he become an ordained Episcopal priest. The Anglicans believed Stiles catholic creed and his deism beliefs were acceptable and, if he sailed to England, he could be ordained an Anglican priest, then return to lead a Rhode Island church. Ezra turned the offer down.

In 1755 he was invited to preach at the 2nd Congregational Church in Newport. The charm of the second largest port in New England and its growing and diverse populace was strongly appealing. He received a firm offer to become minister. On a second trip, he was showered with attention, his proposed remuneration was increased, and an internal “Voice of Providence” brought his acceptance. In August 1755 he moved to Rhode Island to begin a 22 year career that defined his personality and prepared him well to return to Yale as its 8th President.

Stiles deistic Christianity was perfectly acceptable to his congregation. Accused of Arminianism in the past, Stiles preached a liberal Christianity that required humans to do good work and to accept the divinely inspired Bible as God’s holy word. In Rhode Island he was free of the vicious feuding alive in Connecticut Congregational churches. He tolerated all religions and would willingly contemplate most any intellectual argument on any subject. He was a true intellectual, with a driving curiosity to learn all he could about anything that fascinated him.

Stiles immersed himself in Newport life embracing many friends among merchants, fellow clergy, and his growing congregation. He became a librarian at the Redwood Library - former home of George Berkeley, a renowned philosopher and major supporter of Yale. He maintained correspondence with Yale fellows, and other important people in Connecticut. He built good relations with friends at Harvard and in England. His prolific letter-writing and research built his reputation among the world’s intellectual community.

As minister of the 2nd Congregational church, a house was included. He soon married and began to raise a family. Abigail Sergeant had found a new husband in Stockbridge, so Ezra wooed in New Haven settling on Elizabeth Hubbard, daughter of a physician friend. Ezra and Elizabeth were married in 1757. They raised six children in ten years: five girls and one boy (Isaac.) Unusual for the times, all but one girl survived childhood.

In 1762, a synagogue was built a few blocks from the Stiles’ Newport home. He had only a cursory knowledge of Hebrew and was interested in learning more. He wished to read the old testament in its original form (as he had learned to read the New Testament in Greek.) He befriended Isaac Touro, the chuzzan of the synagogue, developing a long lasting relationship. He translated the Hebrew bible completely in three years. He also learned other semitic languages including Arabic finding it an easy step after mastering Hebrew.