A New Way to Make Robotic Sensors, Based on How the Body Heals Itself

Inspired by the body’s natural wound-healing process, Yale robotics researchers have developed a safer and quicker way to manufacture sensors onto soft, deformable structures.

The method, developed in the lab of Rebecca Kramer-Bottiglio, the John J. Lee Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science, can be used to sensorize soft robots and wearables. The results were recently published in Science Robotics.

The method, developed in the lab of Rebecca Kramer-Bottiglio, the John J. Lee Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science, can be used to sensorize soft robots and wearables. The results were recently published in Science Robotics.

Many soft robotic systems require integrated sensors that can stretch and conform along surface contours. Over the last decade, composite materials made from polymer and conductive fillers have become a popular choice to use for wearable, stretchable sensors because of their ability to upscale the process. However, the manufacturing process can be cumbersome, and the solvents used to make them can be toxic and damaging to the robot or wearer. For instance, applying a typical conductive ink directly to a latex balloon would immediately burst the balloon because of the conventional solvent present in the ink.

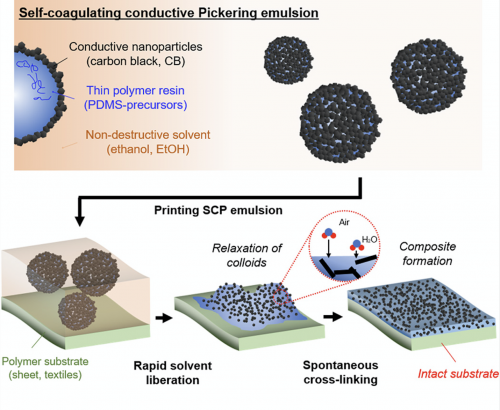

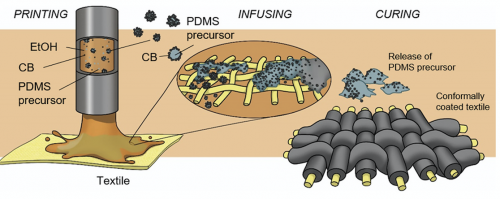

The researchers came up with a process that uses a mixture of ethanol filled with polymer resin particles, which are coated in even smaller carbon black nanoparticles. Upon printing, the polymer and carbon black spontaneously coagulate to form a conductive material, while the ethanol evaporates away. Since the solvent is used as a carrier and not for the purpose of thinning the polymer, safer solvents can be used, which diminishes safety concerns to anyone working with them.

The researchers modeled their method on hemostasis, the body’s system for healing wounds, in which plasma carries blood platelets to be deposited at the site of injury. Because it involves directly transporting microscopic substances and their spontaneous coagulation, it’s a quick and efficient process.

“Analogue to the plasma is the ethanol, which carries the carbon black nanoparticles and the polymer resin, which act as proteins or platelets inside the blood, and those are deposited onto the target, or printed, location,” said Sang Yup Kim, a postdoctoral researcher in Kramer-Bottiglio’s lab and lead author of the study.

The researchers created the compliant sensors by printing the blood-mimicking emulsion ink, known as a self-coagulating Pickering emulsion, directly onto soft polymer materials, including soft actuators and conventional textiles. The resulting sensors were highly sensitive and exhibited low hysteresis, which makes them useable for soft robotic applications and wearable robotic devices.

“We believe this result is a meaningful step towards technology transfer of soft sensors into commercial platforms,” said Kramer-Bottiglio. “The ability to easily print useful sensors onto any substrate using non-toxic, safe solvents makes the process a viable solution for those who don’t have access to specialized lab environments.”